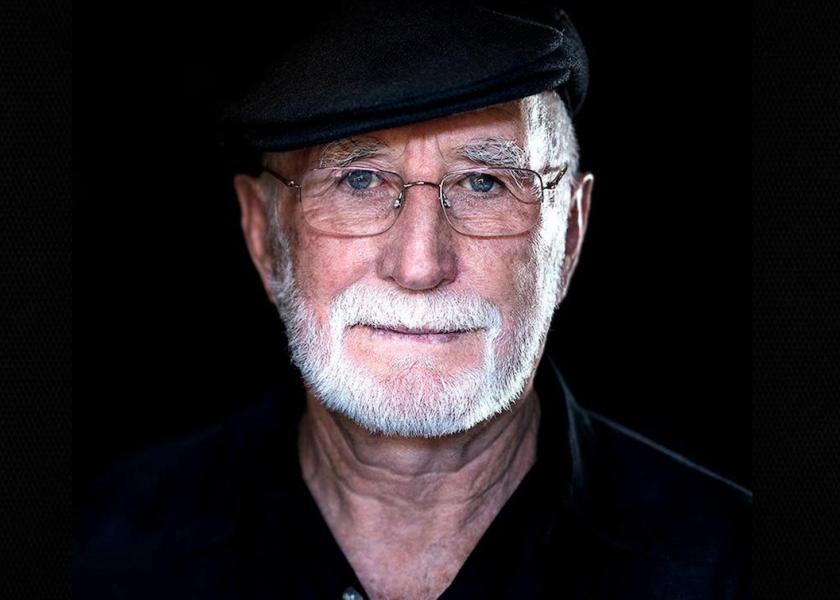

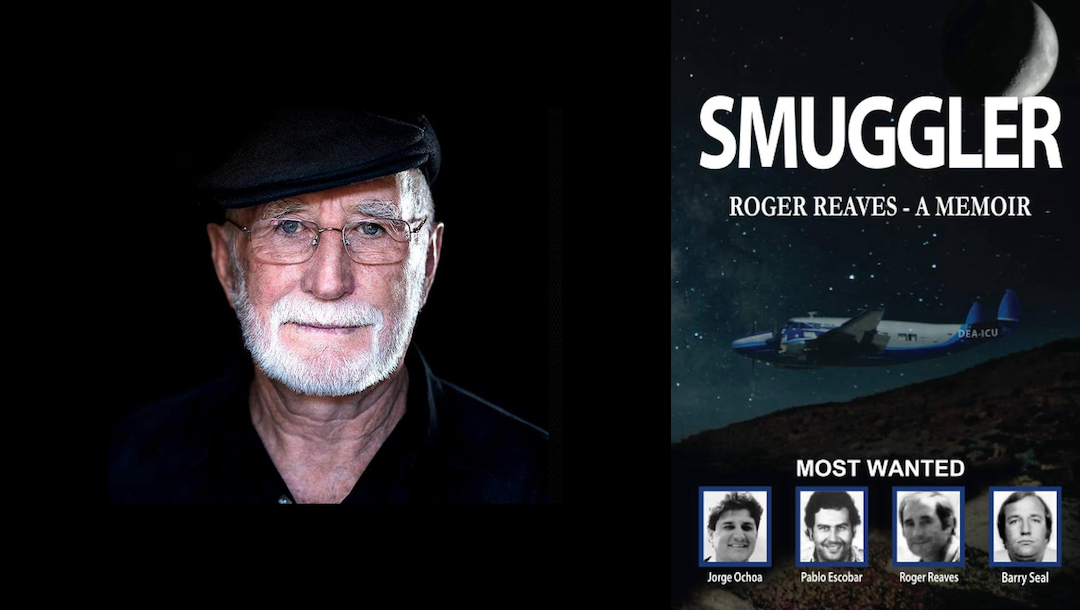

Corn and Cocaine: Roger Reaves and the Most Incredible Farm Story Never Told

Riding a lightning bolt on a silver saddle, Roger Reaves forged the most astounding farm life of modern times as the preeminent drug smuggler of the 20th century. From row crop poverty to moonshine to marijuana to cocaine, he amassed a $60-million fortune as the highest paid narco-pilot in history, carrying cargo for Pablo Escobar and a host of global kingpins.

Reaves was shot down twice in Central America, brutally tortured in Mexico, lost in the Amazon for 11 days, chased down every backroad on the planet, and incarcerated in 26 prisons in seven countries on four continents for 33 years, yet escaped five times.

Despite gaining phenomenal wealth and notoriety, Reaves never intended to leave his fields of corn, cotton, and tobacco. “All I ever really wanted was to be a farmer,” he explains with a heavy dose of humility, each syllable soaked in the smoothest honey of Southern accents. “I had a helluva life even before I transported an ounce of illegal drugs. In many ways, my farm story is tougher to believe than what came after, but it shaped who I am.”

If every man is a novel, Reaves is a library. He is a character beyond fiction, as if Huck Finn fell into the pages of Lonesome Dove and came to life in The Grapes of Wrath. “No matter if I was in the jungle, mountains, desert, or flying over the ocean, I could always hear the farm calling,” he says. “If you want to understand my life, go back to the farm.”

Tapping the Vein

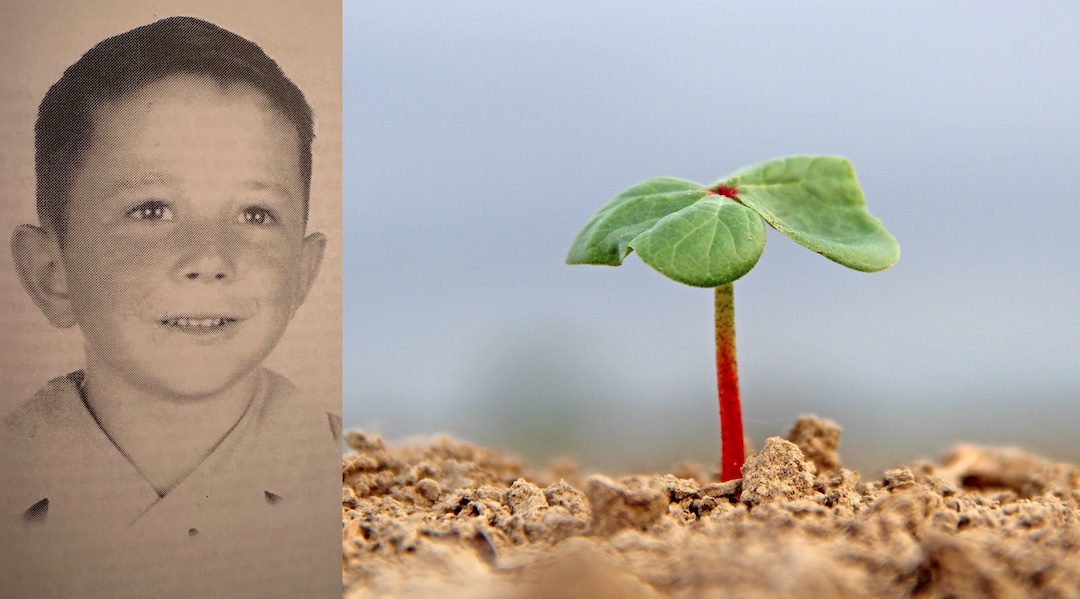

In 1943, Roger Reaves was born to the central Georgia family of William and Hortense Reaves. William was a kind and firm father, and a farmer of the first order. “Daddy picked me up, took one look at his boy, and started bawling,” Reaves says. “He never told why.”

Hortense, extraordinarily beautiful with black curls and blue eyes, yet tough as whip leather, possessed keen intelligence that passed to her firstborn son. “When I was born, momma’s breasts swoll to unbearable pain,” Reaves describes. “Daddy crawled under the house, grabbed several new puppies from his speckled bird dog, slipped socks over their paws and claws, and those pups relieved momma’s hurt.”

In the pocket of Telfair County, the Reaves family set plow to dirt in a closed, rural realm dotted by unpainted, pine sharecropper houses atop bricks and wooden blocks, with swinging, solid-board windows on oversized, barndoor hinges. Spartan. A mule lot out back, corn crib alongside, Model A Ford truck from the late 20s-early 30s parked in front, and maybe a shade tree for the most blessed.

A notch above the sharecropper class, on a washboard road 5 miles north of Jacksonville, the Reaves owned 163 acres. On one side of the lane, behind three mules, the family worked 108 sandy loam acres of corn, cotton, peanuts, and tobacco, along with a tiny patch of sugar cane. Across from the farmland, they lived on a 55-acre stretch of woods and pasture.

Poverty was a given. No electricity. No tractor. No car. Wood-burning stove. Kerosene lamps. A two-hole outhouse with corn cobs—red and white—for toilet paper: red cob first wipe and white cob second wipe to see if another red was needed. A Sears & Roebuck catalogue was at arm’s reach, but the slick pages lacked the scouring power of corn cobs.

During crop season, Reaves wailed unless he could hit the fields with his father. “Daddy wired a board onto our Oliver plow, so I’d have a place to sit. We’d hit a tough patch of dirt and he’d urge me, ‘Ground is getting hard. Sit heavy, Roger. Sit heavy.’ I’d pull up on the board with all my might, convinced my pressure was the difference maker. Some of the finest memories of my life were in those fields with my daddy and his mules: Mike, Cora, and Slow Kate.”

Reaves, alongside seven brothers and sisters, ran barefoot all year, except for shoes at school and church. Sporting closely cropped black hair and baggy, blue overalls, he ran an endless maze of woods and bottoms in proximity to cousins, uncles, and aunts—the last of the family reserve, a mix of blood and water relatives, many of whom were holdovers from the previous century.

“My paternal grandparent’s house had bare pine lumber, a high-pitched roof, and cypress shingles,” Reaves recalls. “It was dark inside except for light shooting down from holes in the roof. Their clothes were hung on racks and covered by cowskins to always keep them dry. On the walls, small, cloth bags of garlic, sulfur, and strange ingredients hung on nails—kind of like magic to ward off disease.”

Visits to his aunt, Sadie Reaves, were even more surreal. Well into her nineties, Sadie often sought the services of a local pseudo-doctor, an expert with the blade and a specialist in bloodletting. On a long, creaking front porch draped in weeping wisteria vine, Sadie received the doctor in her rocking chair, arm propped at the ready. “The quack would bleed her good,” Reaves explains. “He’d slice a vein and the blood flowed—dark crimson dripping deep into a white enamel pan.”

Further down the dirt road, in relative isolation, lived Reaves’ cousins, Annie Parrish and her mentally ill younger brother, Charlie. Annie died unexpectedly inside the house, seated in a chair—undiscovered for weeks in the heat of summer. “The vultures literally gathered on top of the house from the stink before anyone noticed she was gone,” Reaves says. “When the authorities came and tried to get her out of the chair and into a body bag, she fell into parts.”

Death Knocks

River over a rock, stories cascade from Reaves. At 82, his ability to paint with words is remarkable. Throw him a tiny bone and he returns a massive meal—a never-ending tapestry of people, places, particulars, and peculiarities, all delivered with an easy, warm laugh, quick smile, and sweet cadence.

Simply, Reaves is a born raconteur. “As a boy, I loved to hear great stories. I was all ears and I listened better than everyone else. Every detail mattered; even the voice mattered.”

“You can tell a lot by a voice, by the way of delivery,” Reaves continues. “Even today, I can learn everything I need to know about a man just hearing his voice. Truth or lies are there.”

From his earliest years, Reaves believed he was different from other children. Calm in crisis. Calculating in the moment. “Deep inside, I knew I wasn’t normal, but until later in life, I never realized how different and wild my existence was on the farm.”

Reaves’ adolescence was a composite of countless, overlapping vignettes—Tom Sawyer brought to life in a theater of the surreal. Setting trotlines; attending cock fights; chasing wild pigs; catching cottonmouths and coachwhips; taking a string of bream to momma; watching the plow bust clods while killdeers skittered in front of the mules; poking holes with an iron buggy axle below near-fossilized lighter’d stumps to set dynamite; shaking poison-filled flower sacks in the rows as white dust layers caked on ghostly skin and hair; running a 25-cent watermelon stand at 5 years old; marveling over the purchase of a John Deere MT tractor at 7 years old; turpentine brews; blood feuds; towering yellow pines 100’-plus tall and 4’ wide; yard brooms made of gall berry bushes; tales of Grandpa Lee Reaves killing a man in open court—shooting him twice in the chest and setting the pistol on the judge’s bench—and sentenced to 15 years of hard labor, but pardoned after going blind in a prison medical experiment, and more. Volumes more.

“Maybe it was poverty; maybe it was farming; maybe it was my environment; maybe it was my DNA. There are things you’re imprinted with and things you’re born with that you can’t discover for years. One thing for certain, I was born with abnormally sharp instinct. I had premonitions of what was to come.”

Premonitions. In 1952, seated in a patch of grass on Highway 441 alongside a bridge over a fishing hole, geared with cane pole and can of worms, 9-year-old Reaves felt the tug of dread. Obeying a palpable pull to flee the scene, he crossed the road for home, just before a flatbed truck carrying a sawmill motor rumbled down a dip toward the bridge: three men in the cab and five men laughing in the bed around the motor.

“All eight of the men were smiling and joking, enjoying life. There was a settling of the road just before the bridge. The front tires hit the spot and the truck went about 4’ in the air. The driver lost control and it was over. Men were tossed everywhere, even over the banister. The motor tumbled and smashed into the ground in the exact spot I was sitting minutes earlier.”

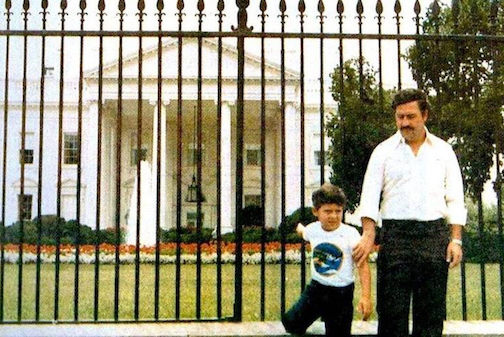

The boy who would one day ride horses, drive cattle, dine, and talk farming with Pablo Escobar—the most notorious drug lord in history, worth at least $70 billion in modern equivalency—was spared from death.

“I didn’t die that day because I listened when I was told to move,” Reaves says. “That was a guardian angel—the same one that protected me so many times throughout my entire life. Anyone would believe me if they saw the body parts slung over the road and bridge.”

The Lunatics

In the late 1950s, Reaves sacked groceries at a general store every Saturday for 14 hours, hitchhiking roughly 20 miles north to McRae. “Life was a struggle and it created an atmosphere where strange people entered or exited the scene. I remember all kinds of wild people, but there was a particular couple that stays fresh in my memory—the lunatics.”

Walking Highway 441 on an early morning, Reaves watched as a light gray, four-door sedan eased to the shoulder. He climbed in the back seat behind the driver and noted an incongruous pair: a clean-cut man decked in a crisp suit at the wheel, and a dowdy woman in the passenger seat—her face covered by a light-colored towel stained red in patches.

The man offered a bright greeting; the woman sat silent as a stone.

Hanging beside Reaves, directly behind the woman, was a brand-new suit. The man turned to Reaves: “Do you want to buy this suit—$5?”

“No thanks. I don’t even have $5,” Reaves answered.

In a flash, the woman peeled off the towel and exposed a bleeding, swollen face. She burst into explanation, telling Reaves the man was released from an insane asylum one day prior and the orderlies hadn’t “cured him one bit.”

Reaves’ skin crawled. He couldn’t discern who was crazy. Him, her, both?

The man drove in silence for several miles, until the vehicle passed a rest stop where a family was cooking a roadside breakfast: father, mother, and two teen daughters wearing shorts.

“The driver turned his head to look at the family, just like I did, but the passenger woman went nuts,” Reaves recalls. “She started screaming: ‘You’re a sunuvabitch. Look and lust because that’s all you can do.’”

With those words, the man struck the woman in the face with the back of his fist, hard enough to rock her against the sedan’s window. She draped the towel back over her head and slumped in submission. On they drove—again in silence—almost to McRae.

“Just before McRae, there was an old gas station called Nubby’s, because the owner had no legs from the waist down—railway accident,” Reaves details. “Nubby had been convicted of raping his own mother and the state locked him up for a long time. Anyhow, of all the places on the highway, that’s where the lunatics pulled over.”

“Right at Nubby’s, the lady started cussing the driver again, accusing him of all sorts of unmentionable crimes. He pulled into Nubby’s lot, turned off the vehicle, and started beating the hell out of the lady. He was trying to murder her, but she sat back and took every fist—never raised a hand.”

Bewildered, but convinced the woman would die, Reaves grabbed the man from behind and pulled hair and neck. “I felt his windpipe against my hands and arms; he kicked so hard the radio dials broke off. He slumped, and I hollered at the lady to run. She sat there silent, like her switch was turned off. He staggered out of the car, making choking noises, and stumbled into some woods beside the station. He had no idea where in the hell he was going.”

Reaves ran down the highway and alerted the sheriff. “The sedan never moved from Nubby’s for a month and then one day it was gone,” he says. “What happened to the lunatics? I don’t know and sometimes it’s better not to ask questions.”

Alone

Liquor drains many a farmer.

In the mid-1950s, Reaves’ father, William, pulled hard on the bottle. “I’d say he was a full alcoholic by the time I was 10. It reached a point where he loved liquor more than life.”

In 1957, during William’s descent into addiction, Reaves was stoked to sell a bumper crop of his father’s watermelons. The father-and-son pair loaded a semitrailer of black diamond melons packed 5’-deep in straw. Macon to Atlanta to Chattanooga (Tenn.), they sold almost the entire haul for a hefty knot of profit. On the final night of market, in Chattanooga, young Reaves crawled into the cab, covered himself in burlap bags for warmth, and fell asleep, while William walked away to drink with a couple of back-slapping locals.

By morning, William’s pockets were empty—robbed of an entire season’s gain. “My daddy was so ashamed,” Reaves recalls. “We had 47 watermelons left to our name in the trailer. We sold them and used the money to buy gas to get home.”

In 1961, at 54, William suffered a stomach aneurysm. Fading fast, William called each of his seven children to his bed. “I asked my daddy about his soul and if he was right with Jesus. I was crying my eyes out,” Reaves recalls. “He told me, ‘Roger, I don’t mind dying because I know you’re there to look after your mother and everyone.’ He was a wonderful man and father, but the bottle took him at 7 o’clock that evening.”

Reaves, a firstborn son, was alone on the farm. Very soon, he would need to kill a man.

Commode Cleaner or King

Larry McMurtry’s seminal Lonesome Dove character, Woodrow F. Call, is reborn in Roger Reaves: Polite to a fault, yet incapable of disregarding rudeness or slights. Reaves is slow to draw moral lines, but once the markers are laid, he adheres.

“I’m good to all, but don’t mistake kindness for weakness,” he describes. “I’ll sit on a bench and if you sit down and push against me, I’ll slide over and maybe even give you the money in my pocket. If you take up even more room, I’ll slide down even more without a word. But please don’t push me off the end of the bench. That’s the place you don’t want to go.”

“I’m a Christian, but I’ve never turned the other cheek very well,” he adds. “I’ve got thin skin and when somebody insults me, I remember that. Maybe that has to do with a stigma about growing up poor on the farm, maybe not, but that’s who I am.”

Despite a lifetime rubbing elbows with shakers, movers, and drug lords of every stripe, Reaves never forgets his origins. “Commode cleaner or king, I always treated everyone the same. You either lie or you don’t, and there’s no such thing as half-honest. You’re either a snitch or you’re not. You’re either pregnant or you’re not. There are certain lines you either cross or you don’t.”

On March 31, 1961, Reaves’ sister, Charlotte, 16, readied for her first date. Charlotte and her cousin, Barbara, were taken to the movies on a Friday evening by two teenage boys from Coffee County. Several hours later, Charlotte returned home in severe distress.

“Her dress was torn, and her chest was scratched and clawed,” Reaves notes. “The two boys had taken our cousin home, and then attempted to rape my sister. One sat on her head and the other tried to have his way. She fought so hard he couldn’t complete the act.”

“It wasn’t complicated. I would kill the sunuvabitch.”

Bliss and Blood

Vengeance on April 1. With no wheels, Reaves set out on foot, searching for a plan of action. He walked into Jacksonville, caught a ride with a buddy, and drove over the Ocmulgee River to a skating rink in Red Bluff—momentarily reducing his rage.

Inside the rink, roughly 100 people circled, and to Reaves’ utter surprise, he spotted the boy who assaulted his sister. “There he was, right in front of me,” Reaves recalls. “I saw him going around and around with a girl in a long, white dress.”

Intentions hidden, Reaves coolly walked to the concession stand, dropped a dime on a drink, and reached into the freezing slush of a Coca-Cola ice cooler, pulling out a dripping bottle. He rubbed away the moisture with a towel and proceeded to the skate floor as the blissful radio hit, “It’s A Cotton Candy World,” echoed across the rink:

Every day is a day of wonder never ever blue,

It's a fine and dandy cotton candy world with you.

“I walked onto the floor and he came around once on the inside, then he came around again and I caught him. I swung as hard as I could with the bottle and hit him right between the eyes. His skates went up toward the ceiling and he skidded about 30’. I was running right behind and when he slowed, I laid into his face and beat him to bloody pulp. I couldn’t tolerate his kind of abuse.”

“There was blood everywhere, like a hog had got slaughtered,” Reaves continues. “The rink owner jumped in, but slipped in the blood and broke his glasses. Somebody pulled a knife and cut off the boy’s skates, and they drug him outta the ring.”

The surrounding crowd, frozen with hands over mouths, watched as a bloody Reaves regained his composure. “Roger, Roger,” several voices hollered. “Why did you do that?”

“April Fool’s,” he muttered, calmly walking toward the exit, with the sounds of “It’s A Cotton Candy World,” still hovering in the background:

You're the prize I won,

You're the apple on the stick.

Upon his arrival at home, Reaves’ sister, Charlotte, immediately understood the implications of his blood-stained clothes.

“He ain’t dead,” Reaves said, in a measured tone. “Just almost.”

The Bear

Twenty bucks a day cropping tobacco in Canada? Massive money.

Farms in Canada’s tobacco belt paid $20 per day, plus room and board, for hands—essentially a six-week season that bookended Reaves’ tobacco window, considering his crop typically was in by the beginning of July.

Belongings crammed into a pasteboard suitcase with a wire handle, thumb in the air, he set out for Canada, hitchhiking the East Coast to Niagara Falls and into Ontario.

“The tobacco work, the money, and the fellas I worked with were great—but I didn’t know it would all lead to the blessing of my life.”

During an off day from the rows, Reaves and several coworkers went into Tillsonburg, perched above Lake Erie, for a visit to the fall fair. Milling through the crowd, they passed a tent fronted by a large, bearded man with a loudspeaker baiting the passersby to take on his black bear in a cage: $500 to anyone who could wrestle the muzzled, blunt-clawed bear and get all four of its paws off the ground, and $10 to anyone who entered the cage and tried.”

“Sure, I’d do it,” Reaves remembers. “The bear looked small, sitting over in the corner. I was game for at least an easy $10. I’d grabbed plenty of hogs. Why not a bear?”

Sporting a white shirt and black slacks, Reaves stepped toward the cage. The bearded man chuckled and tossed an inquiry: “Where are you from?”

“Telfair County, Georgia,” Reaves drawled.

“I mighta known,” answered the bearded man. “These yellow-bellied Canadians are afraid of my bear.”

Greeting completed, the crowd surged as the man bellowed into the loudspeaker: “145-pound man against 600-pound beast.”

The cage door slammed behind Reaves. It was on.

“The bear got up and I couldn’t believe his giant size—ever bit of 600 pounds. I slammed right into him and things went wild. The cage bars and floorboards were purposely loose to make maximum noise, and the crowd went out of its mind. The bear hit me at the knees and laid me out. I kicked up as hard as I could into its muzzle, striking a lucky shot that instantly drew blood and made him crazy, and he mauled me all the more,” Reaves says.

“The bear was cut bad, out of control, and I was scrapping for my life—it was bloody and foamy and wasn’t the tidy, pre-planned performance that was supposed to go down.”

Infuriated, the bearded man entered the cage and snapped a chain on the bear’s neck, just before the animal turned on the owner, exploded out of the cage into the crowd, dislodged several support poles, and pulled down half the tent before getting wedged in the tangle.

Clothing in tatters, Reaves staggered from the cage and asked for $10.

The bearded man growled: “Go to hell.”

Carried back to the tobacco farm’s bunkhouse by his friends, Reaves was bedridden for two days in recovery—a loss of $40 in field pay, as well as his only set of street clothes.

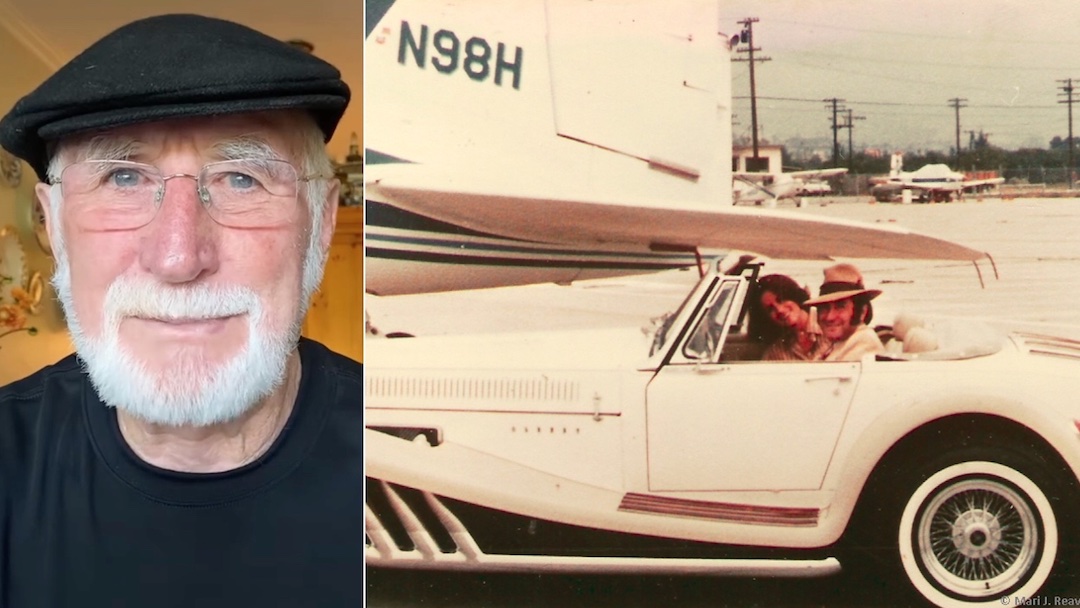

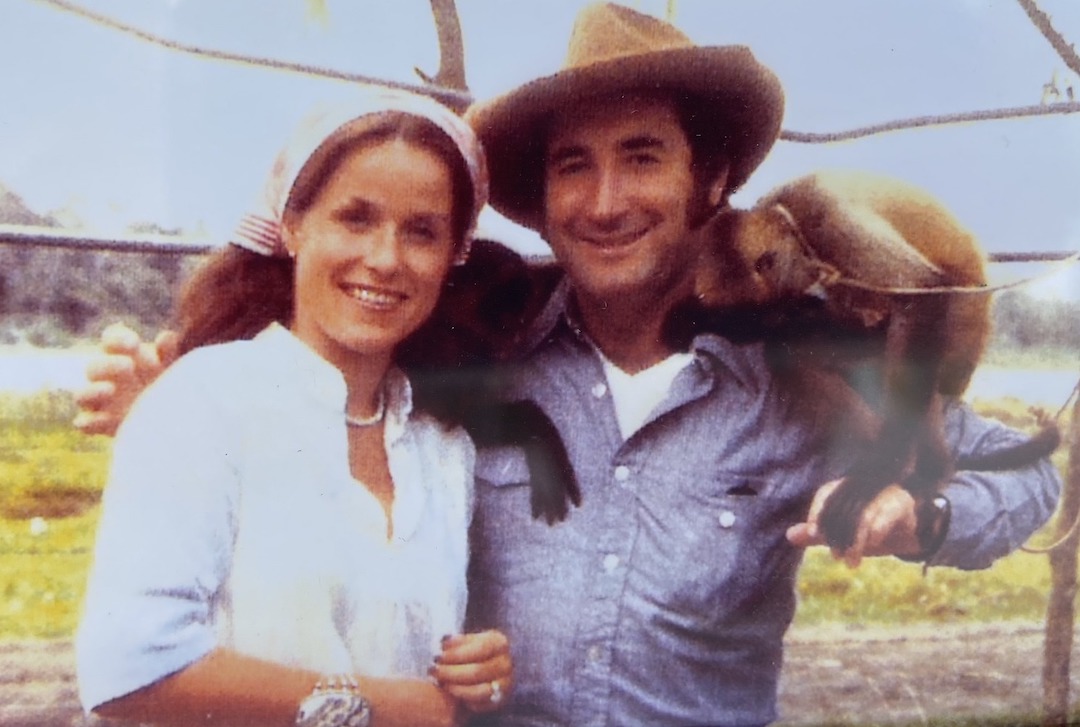

A week later, hobbling with a cane, Reaves took an after-work trip to Turkey Point Beach at Lake Erie. He walked the pier and met Marrie—"destiny.”

“I got to the end of the pier and there were three girls sitting on towels, including Marrie, who would become my wife. My one and only. I am that fella who believes in destiny.”

“That was 63 years ago and Marrie is just as pretty as the day I met her. I could never, never have found a better wife. A saint. She prays for people and is a devout Christian, and her prayers are answered. Through all the peaks and valleys that were to come, she stood by me.”

Reaves married Marrie, and the newlyweds hoped for prosperity on the Georgia farm. In short time, they were as broke as a stick-horse.

White Lightning

Learning to fly was the Lord’s work. As a late teen, Reaves read Through Gates of Splendor, the best-seller about an attempt by aviation missionaries to reach a tribe in the Ecuadorian Amazon. “I wanted to do that: fly supplies in and out; fly sick people to hospitals,” Reaves says.

“I paid $10 to a crop duster in Douglas to start my flying lessons and I got hooked. It was a skill I had no idea how much I’d use later.”

Truly. Only a handful of years in the future, Reaves would fly across Latin America and the world, but his cargo would be marijuana instead of missionaries, and cocaine instead of clinical supplies.

In the interim, Purina was promoting poultry around Telfair County. Reaves went all in, urging Hortense to mortgage the farm for 36,000 laying hens. It was a bold move, but Reaves drowned in debt. He caught the wrong end of the market wave and got buried under $78,000 in chicken feed.

“So many farmers we knew were losing their farms in our area in the 1960s and I remember a couple of suicides,” Reaves notes. “It was terrible, desperate situation for a lot of families.”

In 1966-67, facing a potential farm loss, Reaves turned the chicken feed into moonshine—1,000 gallons per week. Packed in 200-gallon loads into the back of a long Buick with no reverse, Reaves delivered the firewater to eager customers in Waycross and Douglas. The bootleg cost him $1 per gallon and sold for $3 per gallon—approximately $2,000 weekly profit, contingent on the weather.

“It was risky business because the police would shoot you dead over illegal liquor. Sure enough, a competitor—another moonshining farmer, big acreage—turned me in. The revenuers showed up with bloodhounds and shot at me 40 or 50 times while I ran into the woods with the bullets snapping and swum a mile down a creek to escape.”

Soon after, Reaves turned himself in and was splashed on the pages of the Macon Telegraph, Atlanta Journal, and Telfair Enterprise: “Largest moonshine still in county history found near Jacksonville, Georgia. Four vats containing over 40,000 gallons of mash, 500 gallons of pure moonshine, 200 butane bottles, 12-foot condenser. One man arrested and sheriff says there will be more to follow.”

The grand jury deadlocked. Reaves refused the government’s offer to turn rat, but skinned to the bone, he lost everything that had wheels: pickup, tractor, International L-170 truck, and farm equipment. “Everyone knew what happened and I wanted no part of anyone at church or the store because I was ashamed. And I was paralyzed broke.”

Adios. It was time for Reaves to walk away from the fields of his childhood—forever. His slippery escape from the law and his refusal to turn informer foreshadowed the remainder of an incredible life.

“I hit the highway and I had tears in my eyes. In my head, I was leaving to go make money to pay off debt and farm the next spring. My spirit knew otherwise.”

Cropping days done, the poverty-stricken Georgia farm boy was about to tap El Dorado: “Imagine if you were in a casino with the slot handle pulled down and gold coins were flooding out, tumbling while you bagged,” Reaves asks. “When would you let go?”

Mercury or Marijuana

Almost 2,400 miles across the continent, the booming California economy of the early 1970s beckoned—particularly $7 per hour construction labor. Framing, concrete, electricity, and firefighter—even a short stint on a fishing boat in Alaska, Reaves bootstrapped for his bread, keeping an eye open for another dollar. Initially, he found significant side-stream income in antiques, locating an abundance of relics in Los Angeles County and far beyond—including the Midwest. The antique business was a plum to peel: Buy cheap, haul to California, sell to the nouveau riche.

One by one, Reaves paid off his Georgia farm debts, with enough cash flow left to buy his first airplane, a Cessna 182—the trusty Volkswagen of the sky.

In 1971, getting a tip on a motherlode of antiques in Joplin, Missouri, Reaves and a friend rented the biggest U-Haul on the market, latched on a trailer, and packed both to the gills with old furniture. Rolling across the Southwest, riding shotgun, Reaves thumbed the pages of a National Geographic magazine and came across a curious factoid: Mercury, he read, was 13 times more expensive in the U.S. than in Mexico.

Reaves blurted out his thoughts in the cab: “I’m gonna fly to Mexico in my airplane and buy some mercury and bring it back for a big profit.”

Reaves’ friend, the driver, responded with a life-altering question: “Mercury? That’s too heavy. Why don’t you fly marijuana?”

Need a Co-Pilot?

Life was sweet. Reaves had Marrie at his side, two baby girls, two houses, an airplane—and hopes of a farm. Yet, he was staring at an offer to fly the Cessna 182 to Mexico, fill the back seat with marijuana, fly back to California, and pocket $10,000. Lock, stock, and smoking barrel.

“And just like that, I made the flight and had a bag filled with $10,000 in cash. Intoxicating. So easy. There wasn’t even such thing as DEA watching the border.”

Faster than henhouse gossip, Reaves made a second flight to Mexico—another $10,000 in crisp bills. Why not buy a bigger plane, bigger loads, bigger money?

“I started thinking long-term and asked a lawyer friend what the penalty would be if a fella got caught: probation or four months raking leaves.”

Following the ball, Reaves bought larger wings (a Cessna 207 for $55,000) and began making marijuana hauls for $40,000 per flight. The pot was his path back home: “I drew a line at $300,000. As soon as I made $300,000, I’d quit and we’d go back to the farm.”

Best laid plans. Subtly, dollar by dollar, the farm return faded.

“I made the $300,000 so fast it made me dizzy. I wanted to go back so bad, and I could hear the farm talking to me, but the farm got fainter as the money talked louder.”

Pockets bulging, Reaves gifted his mother, Hortense, a California vacation. He picked her up at the airport in a Cadillac and drove her to Disneyland for a cash-flash afternoon.

Without skipping a beat, she threw a fastball to her son: “What are you doing, boy?”

Reaves answered truthfully: “I’m hauling pot, Momma.”

“How much are you making?”

“I’m making $40,000 any day I want to go to Mexico,” Reaves responded.

“Son, do you need a copilot?”

Banded and Ironed

One-hundred loads of pot later—flown in bigger and badder airplanes, Reaves’ reputation was stellar in the narcotics underworld. His farming background and dependability distinguished him from other mules. “Farming had a huge influence on my performance in the drug trade. I got the nickname of ‘can do’ because I could weld it, wire it, hotwire it, build it, change it, or drive it.”

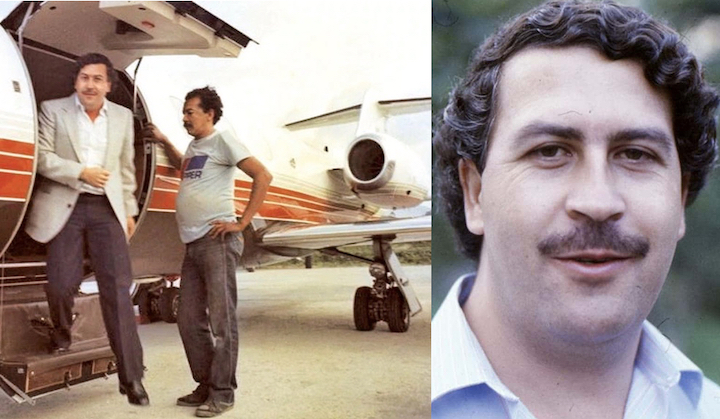

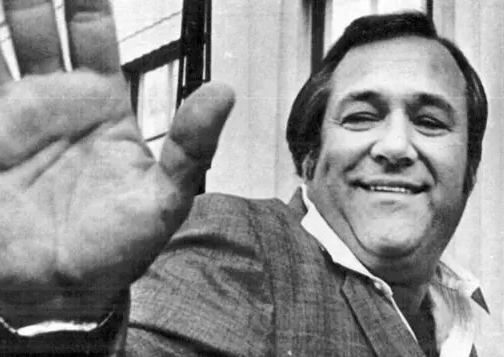

In 1976, a rising Pablo Escobar and Jorge Ochoa, the most infamous drug lords in history, were seeking a pilot for the Medellin Cartel. Escobar caught a tip about an American who kept his word: Roger Reaves. Less than a decade after walking out of cotton and tobacco rows in Georgia, Reaves was summoned to a coca plantation in Colombia.

“I went through a gate to a tiled farmhouse that was 200 or 300 years old,” Reaves describes. “There was a hitching rail and maybe 25 people gathered outside wearing fedoras, all cocaine men.”

Inside the house, Reaves was ushered into Ochoa’s office. “Ochoa was standing beside this big, big desk with 12 big phones lined up in a row, each a different color. He told me each phone was connected to a key U.S. city—Chicago, Houston, and so on. Ochoa was the brains of the operation he said the men outside had 100 tons of cocaine they wanted to move. Essentially, Ochoa would guarantee their drugs like an insurance company.”

Brass tacks, Ochoa asked Reaves a direct question: “What airplane do you have?”

“I have a DC-3, Beech 18, Aero Commander … whatever plane you need, I have,” Reaves answered. “I can get the job done.”

Ochoa signaled a female assistant who walked to a back room. She returned with a man in khaki pants and plaid shirt, pedestrian in appearance. “I shook hands with a man who looked like he could have fit with the crowd; looked just like the rest of us. The man was Pablo Escobar.”

The godfather of cocaine offered Reaves $5,000 per kilo.

Escobar declined to speak English, but Reaves navigated with broken Spanish, assuring Escobar he could glide past the U.S. border. Escobar’s response was plain, according to Reaves: “We’ve got all the work you can do.”

Without a hiccup, Reaves transported his first load of cocaine for Escobar, Ochoa, and the Medellin cartel in an 8-hour flight to the U.S.—300 kilos for $1.5 million in banded and ironed bills. (At peak, Escobar was reportedly generating $420 million per week in cocaine profit and spending $2,500 per month on rubber bands to organize the piles of cash. According to his chief accountant, Escobar lost $2.5 billion in stored cash per year due to rat consumption or water damage.)

“It was just that easy and when I finished, I asked Escobar, ‘When do you want me to come back?’”

“His answer was simple and polite, ‘We’re waiting on you, Senor.’”

Rip Van Winkle Awakes

Reaves made millions upon millions at a pace of his choosing. He hired Barry Seal (portrayed by Tom Cruise in the film American Made) to transport 500-kilo loads generating $2.5 million in pay: $1 million for Seal and $1.5 million for Reaves. However, far beyond Escobar and the Medellin Cartel, Reaves charted one of the most buck-wild tales in American history. (See Reaves’ memoir, Smuggler, for the phenomenal story of his experience in narcotics transport.)

Asia, Africa, Australia, Europe—by airplane or yacht—he smuggled hashish and cocaine to every cranny and crevice on the globe for roughly a decade, risking life and liberty at every stop. Reaves doesn’t deny the motivation: “I did it for the money. Yes, there was genuine excitement and major thrills in flying over shark-infested waters, or getting chased, or beating the system, but bottom line, it was about money. I made around $60 million in 10 years.”

What did Reaves do with the money? He bought airplanes, boats, homes, toys—and seven farms.

One farm—702 acres adjacent to President Jimmy Carter’s operation in Plains, Ga.—paid invaluable dividends. Serving a life sentence for drug smuggling in Australia, Reaves wrote a letter to Carter.

“I explained that I was his neighbor and I asked him for help. I asked for a parole recommendation letter. He wrote to the top of Australia’s government and asked them to consider me for parole. I can’t prove it, but that farm connection probably helped get me out of prison for the last time.”

In 2019, after 18 years (33 years total for nonviolent crime, served on four continents) in Australian lockup, Reaves was free. “I cried three days in a row when I got out of prison. Rip Van Winkle finally woke up. It was time to live because I had Marrie, the most wonderful woman in the world, plus my daughters, waiting on me.”

Would he do it all again?

“No. No. No. I’d have kept us on the farm somehow. I’d have learned to cruise timber or grown Bermuda grass with my chicken houses. There was opportunity, even in farming at the time, but I didn’t see that as a young man.”

“Sure, all the money made me happy, but only in the moment—nothing lasted. It cost me 33 years away from my family. I’d trade every penny I made to get back those 33 years.”

Considering the short lifespans of smugglers and cartel associates, how did Reaves outlive his counterparts by decades as one of the last survivors of a tumultuous era?

“I stayed alive because I kept my word through it all, just like I learned on the farm. Everyone knew I wasn’t DEA or a rat. My daddy taught me to give someone a firm handshake—not too hard or too soft—and look them straight in the eyeball and do what you say you’ll do.”

Reaves no longer looks over his shoulder or listens for footsteps. He is at peace. “I’m so happy now—so grateful for my blessings and my time on the farm. I need nothing because I have my family. The simplicities of life, the fundamentals, are the only things that bring true happiness.”

“I don’t dwell on times gone by, but I also don’t deny the stories from my past. I wrote them down in my memoir, Smuggler, and people understand me a little more when they learn the details. All I ever truly wanted was to be a farmer,” he concludes. “I left the farm, but the wonderful thing is the farm never left me.”

Indeed. The most prolific narco-pilot of all time was a farmer. A life lived like no other: The unbreakable Roger Reaves.

For more from Chris Bennett (cbennett@farmjournal.com or 662-592-1106), see:

American Gothic: Farm Couple Nailed In Massive $9M Crop Insurance Fraud

Priceless Pistol Found After Decades Lost in Farmhouse Attic

Cottonmouth Farmer: The Insane Tale of a Buck-Wild Scheme to Corner the Snake Venom Market

Tractorcade: How an Epic Convoy and Legendary Farmer Army Shook Washington, D.C.