Civil War Sacrifice: Forgotten Farm Boy Was First Soldier Buried At Arlington

Beneath sacred soil, a farm boy was first. Before 400,000 others, a farm boy was first. Preceding a host of other notables into the hallowed ground of Arlington National Cemetery, a farm boy was first.

In 1864, William Christman, 19, and fresh from the crop rows of Pennsylvania, was the first soldier buried in what was essentially Robert E. Lee’s backyard and what would become the largest and most revered graveyard in American history.

William, a mute, statistical curiosity for almost 150 years, is no longer silent. His remarkable story of service mirrors the lives of near-countless young men drawn from the fields of agriculture onto the fields of war. Once a forgotten footnote, William tells a tale of duty, honor, family, and farm.

Pay In Blood

In 1761, Jacob Christman was impaled by a pitchfork to the heart. Jacob had immigrated from Germany 25 years earlier and bought 150 acres of farmland on the Berks-Lehigh county line in southeast Pennsylvania, only to fall foul of a freak calamity at 49 years old.

As cited in History of the Counties of Lehigh and Carbon (1884): “[Jacob] was out in the field on a wagon loaded with hay, he met with an accident by which he lost his life. The horse coming to a gutter refused to cross, when standing on the loaded wagon, he urged him with a hay-fork which he held in his hand. This caused the horse to take a sudden spring forward, and he was thrown from the wagon upon the fork, one of the prongs which pierced his heart, resulting in his almost certain death.”

Scratching out a living in the harsh conditions of a sparsely populated state, Jacob’s descendants continued working in Pennsylvania agriculture into the mid-1800s, when Jonas (Jacob’s grandson) and Mary Christman started a family with the birth of two boys: Barnabus, in 1842, and William, in 1844.

In 1859, with seven children in the brood, Jonas bought 89 acres of timberland—soon to be farmland—in Monroe County’s Tobyhanna Township. Despite the bright prospects, farming in the 1800s was a particularly fickle endeavor, rife with risk. Jonas was struck by severe rheumatism, sold the farm for $125, and then fell off a wagon—incapacitated by a hip injury. Poverty knocked.

On rented ground, Mary showed remarkable mettle, cultivating small acreage and tending livestock, while Barnabus and William worked as laborers on a chain of farm operations growing hay, oats, wheat, and rye atop the Pocono Mountain plateau.

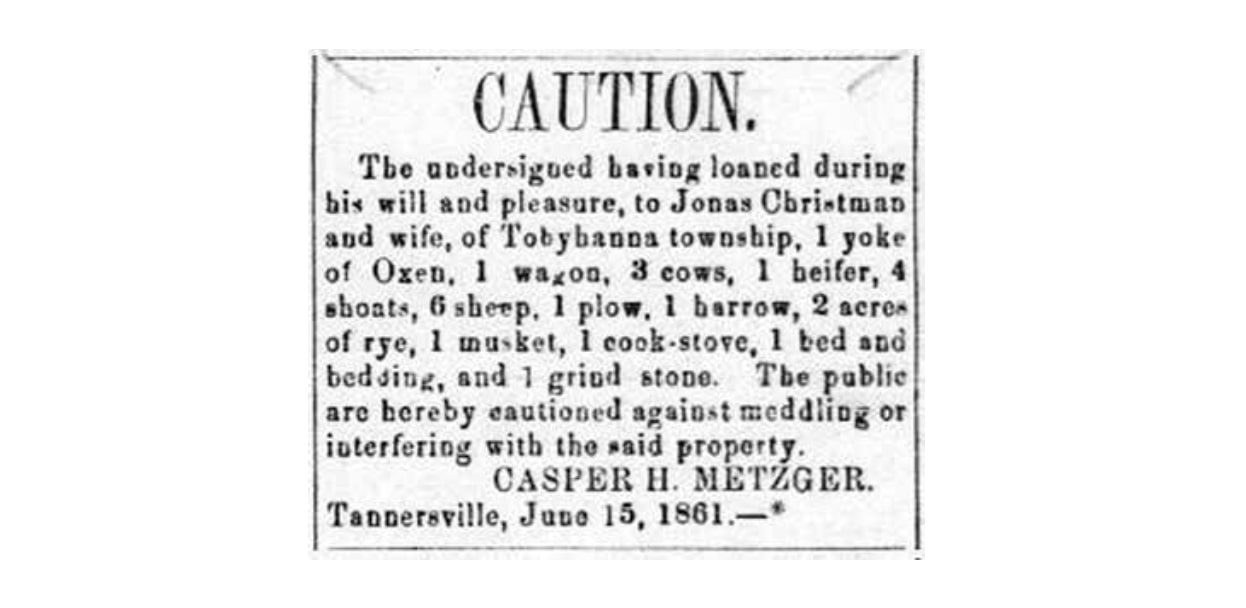

As a window to the family’s threadbare struggles, a newspaper recorded a loan to the Christmans from a local landowner on Aug. 29, 1861: “1 yoke of Oxen, 1 wagon, 3 cows, 1 heifer, 4 shoats, 6 sheep, 1 plow, 1 barrow, 2 acres of rye, 1 musket, 1 cook-stove, 1 bed and bedding, and 1 grind stone.”

The loan date was Aug. 29, 1861, only four months after the start of the Civil War. Barely clinging to farm life, the Civil War would amplify the Christman family’s strain: They would pay in blood.

Invisible Enemy

Half (48%) of Union soldiers in the Civil War were came from an agriculture background. (Likewise, roughly 70% of Confederate soldiers were farmers.) Barnabus, 20, was first of the Christman brothers to take up arms, enlisting at $13 per month in the 4th Pennsylvania Reserve Regiment on June 8, 1861. Pennsylvania soldiers would suffer tremendous loss in the Civil War, with 33,183 deaths, almost a nationwide high, second only to fatalities from New York.

A year after enlistment, Barnabus was killed on June 30, at the Battle of Glendale in Henrico County, Va., struck down in a blitz of hand-to-hand combat across 200 acres of cropland alongside 240 of his Pennsylvania brethren. Barnabus was buried on-site in a mass grave (and later moved to Glendale National Cemetery, designated as an unknown).

Enter William. Rather than bayonets and bullets, William fought an invisible enemy.

‘Thad’ Deed, Land, Money

In 2011, Tobyhanna Township native Rick Bodenschatz began hunting ghosts: Who died in the Civil War in his immediate vicinity?

“I started finding untouched history,” Bodenschatz says. “In our township of 1,000 inhabitants, I found 28 Civil War deaths, and one of those was William Christman. I found out he was buried in Arlington, but I could only find two people in our entire county that had the tiniest bit of knowledge about him. I found his family, but they didn’t even know about him. It was like William had disappeared from history.”

Bodenschatz’s quest to salvage William’s tale turned into a superb book: First At Arlington: The William Christman Story.

By 1864, two years after the death of Barnabus, word of a new draft cycle filtered into Monroe County. Weighing his role as the new family provider, William could either wait for the draft, or volunteer and snag a $300 signing bonus, a plum sum considering undeveloped land could be obtained in Pennsylvania for $1 per acre.

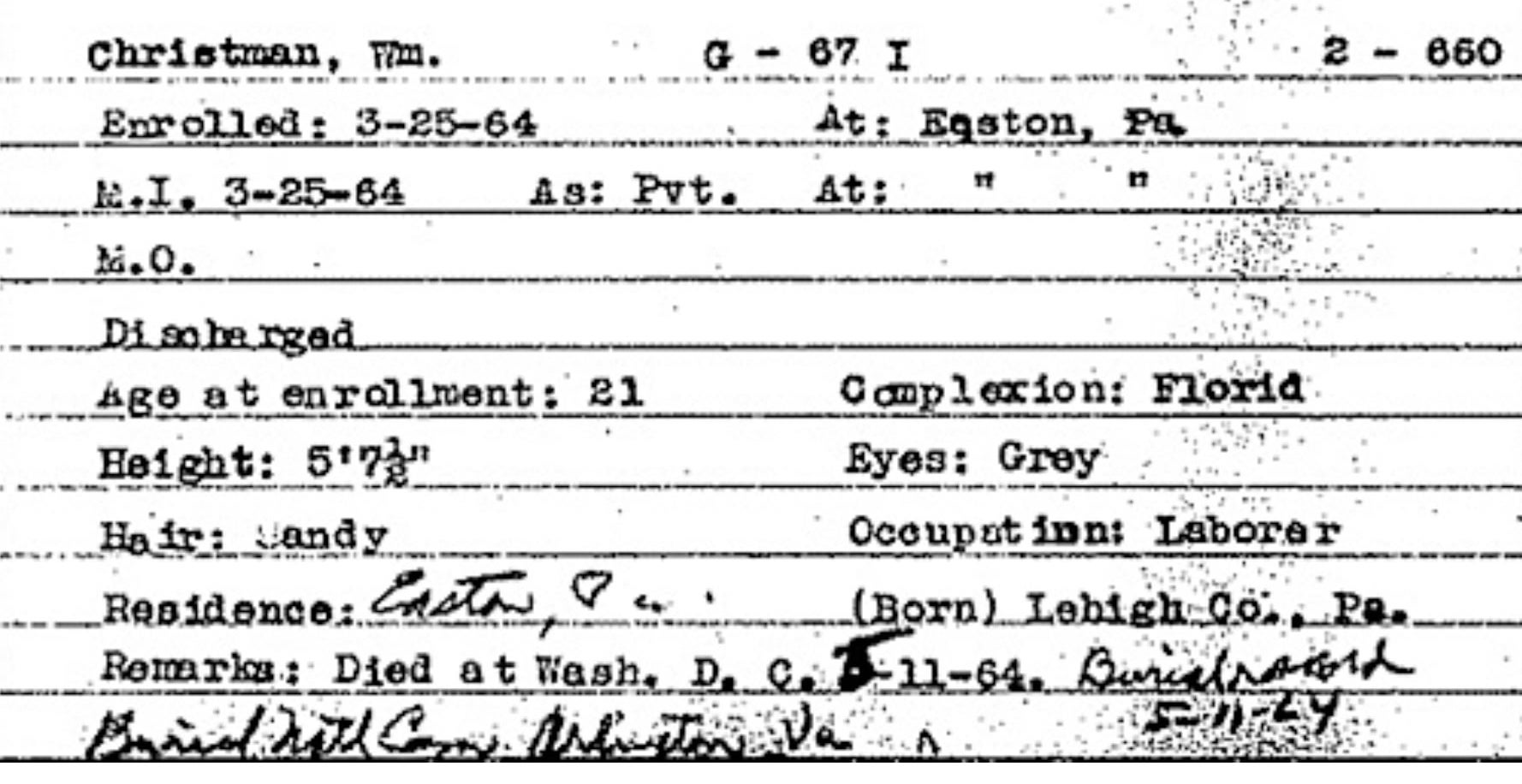

A step ahead of conscription, William signed with the 67th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers. According to his enlistment records, he was 5’7” in height, with grey eyes and a “florid” complexion. Presumably, William’s departure was heartbreaking for his mother, Mary, already dealing with the traumatic loss of Barnabus.

“Mary must have been a special lady,” Bodenschatz notes. “Her husband was ill and injured, but she did everything possible for the family, caring for the children and scraping money together. Without daily newspapers, she may not have known about the immense death totals the Civil War was producing, but she certainly knew her eldest son was dead and her next eldest was marching off to the same war.”

In April 1864, camped at Belle Plain, Va., on the Potomac River, William received a $60 portion of his bonus to be paid in installments, along with $13.41, his first month’s pay in advance. With foresight and concern, William sent the entire load home in a letter to his parents with simple instruction: Buy land.

“... father I want you to write me weter [whether] you have that note from Jacob Stoufer. I want you to take them papers all out put them in My trunk ant keep them their til I com back. father I want you to get thad deed for thad land ant get thad money from Timathy Miller ant pay it on thad land but mind yo thad you get a good deed”

Despite the gravity of his circumstances, William winked at his family with a poetic, but warm conclusion in the postscript of his letter:

So pleas excuse my pour riting

For I hapto write on my plait

So I cant write as good as I ate

Days later, he wrote home again, sending an additional $35 to buy farmland.

“We have to read between the lines, but it’s apparent that William was a man beyond his years,” Bodenschatz says. “When Barnabus dies, which must have been devastating for William, he recognizes the necessity to become the financial supporter of his family. His letters show he was directing his father to pay off land. This demonstrates tremendous maturity and leadership, especially considering William knew there was a good chance he wasn’t coming back from the war and that time was short.”

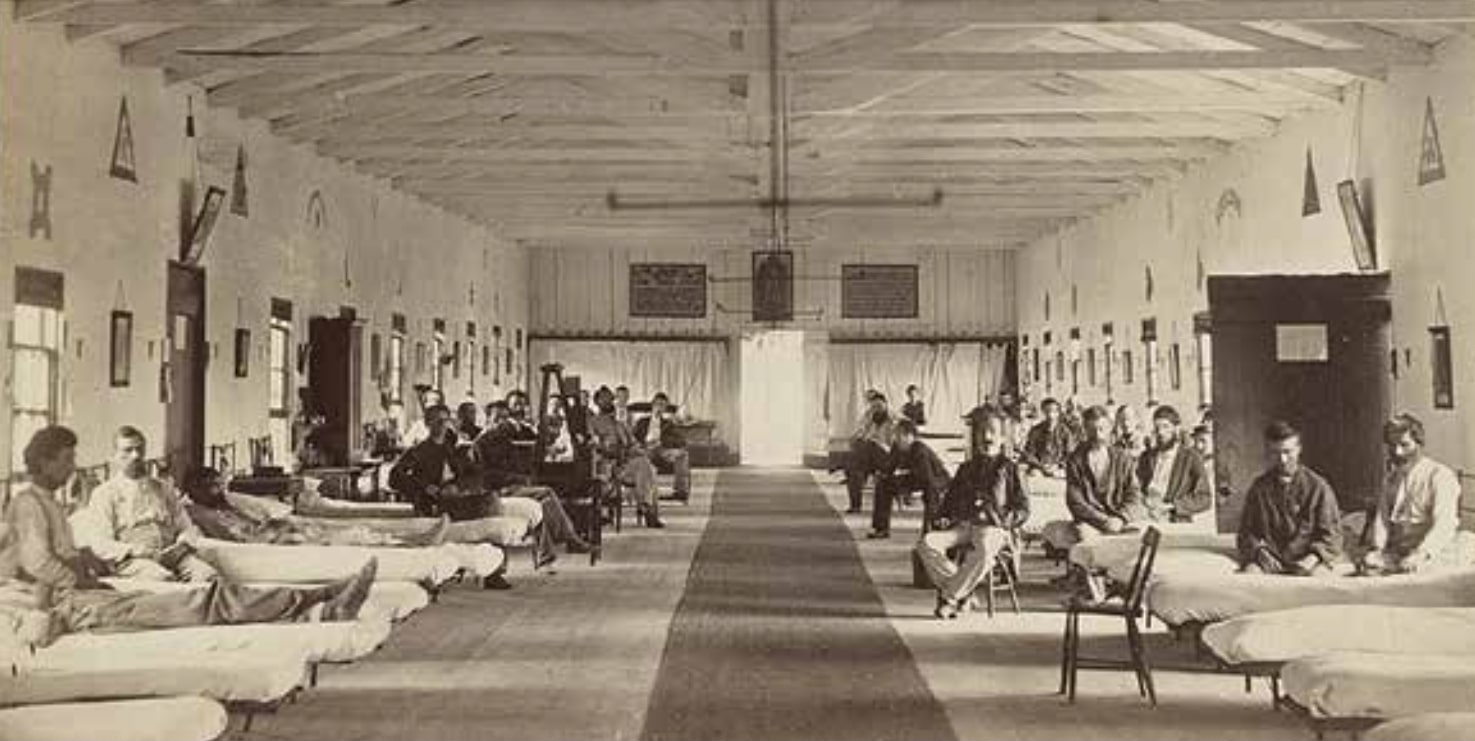

On April 22, yet to see battle, William contracted measles, and eight days later was transferred to a hospital in Washington, D.C. He would exit feet first.

Germ Theory

Warfare was never the same after Joseph Lister.

In 1867, two years after the close of the Civil War, Lister published groundbreaking research on germ theory, providing a roadmap to defeat disease and infection. Prior to Lister’s modern germ theory, at almost every major prolonged conflict of arms in history, disease was the No. 1 killer of soldiers, rather than battlefield action.

As George Washington wrote in 1777: Should the disorder (smallpox) infect the Army in the natural way and rage with its usual virulence we should have more to dread from it than from the Sword of the Enemy.

Or, as surgeon James Simpson penned in the 1860s: A man laid on the operating table in one of our surgical hospitals is exposed to more chance of death than was the English soldier on the field of Waterloo.

The U.S. Civil war was no different. Of 349,944 total Union deaths, roughly 221,000 men died of disease, while approximately 103,500 died in action or from battlefield wounds.

Lister’s medical discoveries came too late for William. On May 11, 1864, while in hospital, he died due to peritonitis, an infection in the abdomen obtained while recovering from measles. William’s worldly possessions mounted to one hat, one shirt, and one pair of pants.

However, with D.C. cemeteries at capacity, where to bury the next round of Union dead? Robert E. Lee’s house, of course.

Soul on Fire

Montgomery Miegs hated Robert E. Lee. Burning zeal.

Prior to the Civil War, Lee and his wife, Mary Custis Lee, lived on a picturesque 1,100-acre estate, Arlington, on high ground in Virginia, directly across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C.

Lee’s father was among George Washington’s most trusted officers in the Revolutionary War, and Lee’s wife was the daughter of Washington’s adopted grandson. The couple’s Arlington mansion, 140’-wide with eight 23-foot-tall columns on the portico, was filled with relics from Mt. Vernon: dishes, furniture, paintings—even the bed where Washington died.

Due to its strategic location and high ground, the Union seized Arlington one month after the Civil War’s start. The Lee family spent decades trying to regain the property. (Lee’s son, Custis, took his claims to the U.S. Supreme Court and won in 1882. Custis immediately sold the Arlington property back to the U.S. for $150,000.)

As the Civil War churned out corpses at the highest rate of any conflict in U.S. history, Congress charged Army Quartermaster General Montgomery Miegs with finding adequate burial ground. Miegs was highly familiar with Lee, having served under him in the Corps of Engineers on the Mississippi River. In a nutshell, Miegs detested Lee with deep animosity and bore a permanent grudge, partially due to Lee’s decision to fight with the Confederacy.

As noted by Miegs’ wife, Louisa: “His (Miegs) soul seems on fire with indignation at the treason of those wicked men who have laid the deep plot to overthrow our government,” she wrote. “He looks so dreadfully stern when he talks of the rebellion that I do not like to look at him.”

Miegs’ called for Lee’s death: "… should be put formally out of the way if possible by sentence of death [and] executed if caught."

With Miegs’ hope of Lee’s execution stayed at least until war’s end, vengeance was still obtainable: Miegs chose to bury Union soldiers in massive numbers around Lee’s estate. And at the front of the burial queue? William Christman of the 67th Pennsylvania Infantry, laid to rest in the northeast corner of Lee’s estate.

However, the periphery didn’t suit Miegs. He demanded burial placements up to the edges of the Lee mansion, encircling Mary Custis Lee’s rose garden. “It was my intention to have begun the interments nearer the mansion,” Miegs exclaimed. “But opposition from officers stationed at Arlington—some of whom did not like to have the dead buried near them—caused the interments to be begun elsewhere.”

By the close of the war, Miegs buried approximately 16,000 soldiers at Arlington, including a 20’-wide by 20’-deep, brick-lined pit beside Mary Custis’ garden filled with the bones of 2,100 unknown soldiers, topped with a monument and four cannons. Miegs made certain the Lees would never be able to disinter such a massive amount of the dead.

Miegs went further, burying his son (killed in battle), wife, father, and several in-laws on Lee’s property. And in 1875, per his wishes, Miegs was buried on Lee’s property. Simply, today there are more Miegs buried at Arlington than Lees.

Obscured by the Miegs-Lee tapestry of animosity, Christman’s body was placed roughly several hundred yards from the banks of Potomac, a half-mile from Lee’s mansion—the first soldier buried in what arguably became the most famous cemetery on the planet. Christman preceded Arlington’s current tally of 400,000 soldiers, including John F. Kennedy, John J. Pershing, Audie Murphy, and Robert Peary.

“Somebody had to be first,” Bodenschatz describes. “It wasn’t a boy from Iowa or Minnesota; it was William Christman. He got a pine box, and although there’s no record, it’s likely a chaplain was present for a proper graveside service of some kind, and a proper paperwork record, and eventually a proper headstone. His sacrifice basically saved the fortunes of his farming family.”

A True Hero

Back in Pennsylvania, William’s father, Jonas, bought 411 acres—thanks to his son’s service and diligence.

William was buried approximately 250 miles from home, and roughly 100 miles from Barnabus. “I doubt their parents were ever able to visit their sons’ graves,” Bodenschatz says.

Several questions linger for Bodenshatz. “If I could meet William, I’d like to ask him what his thoughts were of his family while he lay dying alone at the hospital in D.C. I’d also like to ask him about his memories of the farm community in Tobyhanna Township. History is always filled with names, but I want the personalities.”

“William was a remarkable young man,” Bodenschatz concludes. “Often, people don’t recognize genuine heroes because they are looking for the sizzle instead of the steak. Through my book and research, I hope I’ve ensured William will never be a statistic again. A forgotten soldier no longer forgotten.”

Sincerely. Respect to William Christman, son, brother, farmer, and soldier: 1844-1864.

(First At Arlington: The William Christman Story, is available at the Arlington National Cemetery bookstore or by emailing Rick-boden@msn.com.)

For more from Chris Bennett (cbennett@farmjournal.com or 662-592-1106), see:

American Gothic: Farm Couple Nailed In Massive $9M Crop Insurance Fraud

Priceless Pistol Found After Decades Lost in Farmhouse Attic

Cottonmouth Farmer: The Insane Tale of a Buck-Wild Scheme to Corner the Snake Venom Market

Tractorcade: How an Epic Convoy and Legendary Farmer Army Shook Washington, D.C.