Take Stress Out of Transportation

Transportation doesn’t start with the truck and trailer; it begins where cattle are loaded. Once in the pen it isn’t so much what type of facilities are holding the cattle but how they are handled that matter.

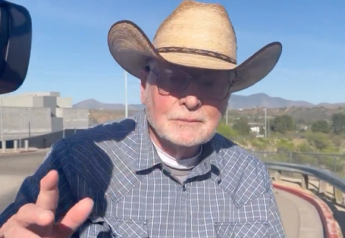

“The design has a limited impact on the welfare of the cattle going through that facility,” says Ron Gill, professor and Extension livestock specialist for Texas A&M. “It is a component, but if we don’t handle the human side most of the design issues are somewhat moot.”

Cattle handled using low-stress techniques will perform better on feed or grass when they arrive at their next destination. Those animals should also have fewer health problems.

For the end stages, handling cattle in a way that reduces stress will help maintain meat quality by reducing bruising and the incidence of dark cutters. Low-stress techniques can also help reduce lameness problems that might result in a non-ambulatory animal unfit for slaughter.

The staging process, right before and during loading, is where Gill sees the best opportunity for immediate changes. If the cattle are brought up calmly to the handling facility they’ll sort off easier into the various compartments on a semi-trailer.

“If we can’t get them to where we can sort them smoothly, quietly and calmly, a lot of the other stuff we do will never really matter because we’ve lost control of the mindset of the animal,” Gill says.

When looking at facility designs, Gill recommends having enough space in the loading alley to bring up the number of cattle needed in a particular part of the trailer. For instance, if a truck can hold 25 head of 800 lb. steers in the belly, bring them all in one bunch rather than splitting the group. He acknowledges some stocker and cow-calf operations might not have large enough facilities to do this, but most feedlots should be able to load in this manner.

“We want enough capacity in the alley to establish flow and get cattle to load all the way through,” Gill says.

Cattle should follow one another like a stream, rather than being pushed from behind. To achieve that flow, cattle must feel like they are going back where they originated from. A tub with a serpentine alley or a Bud Box both achieve this type of movement for loading. Ideally the flow will work well enough so fewer people will be needed to move cattle.

“If we don’t understand the behavior of livestock, we can’t build facilities that will help us,” Gill says.

Reducing incline in the loading ramp will also increase the flow of cattle. Gill recommends having a loading chute at least 16' long, preferably 20', to give the cattle enough incline to walk up and down.

Many of these same principles hold true for loading cattle in stock trailers as well. Designs for stock trailer loading facilities have cattle being forced into the trailer instead of flowing back into the trailer. Gill believes cattle don’t haul as quietly when forced into a trailer. “They’ll haul a lot better when it is their idea to get on the trailer,” he says.

How cattle are loaded plays an important role in reducing stress during transportation. Cattle should be gathered quietly and loaded to maximize animal flow.

Stock trailers are being built to be higher off the ground, making it more difficult to load and unload cattle. Producers might need to make a special inclined area or back trailers over a raised spot.

“Cattle will load so much better if they can walk into a trailer instead of making them jump,” Gill says.

Despite low-stress handling before transport, it won’t stop the stress of actually moving animals to a new location.

Transportation is the single event we put animals through that causes the most stress, says Karen Schwartzkopf-Genswein, a senior scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

Cattle will often be in tight quarters and off feed and water until arriving at a new location. Depending on the time of year, there could be heat or cold stress endured by the animals on the trip. For every 1°C rise in ambient temperature shrink increases 0.04%, she adds.

The length of time in a trailer causes additional shrink. From 10 to 20 hours, cattle will lose 6% to 7.5% in body fluid. At 24 to 28 hours, Schwartzkopf-Genswein says cattle will start to lose tissue, which will set their performance back even further.

“Longer journeys at higher temperatures increase shrink and poor welfare outcomes overall,” Schwartzkopf-Genswein says.

In a study looking at the experience of drivers and the impact on shrink, she found truckers with six to 10 years of cattle hauling experience yielded the least amount of shrink at 4.79%. Drivers with two years of experience or less had shrink rates of 5.09%, while drivers with three to five years’ experience had 5.11% shrink. If a driver had been on the road more than 10 years cattle shrunk 4.86%.

Cattle haulers with less experience had more cases of lameness, non-ambulatory cattle and dead animals compared to experienced truckers. Schwartzkopf-Genswein says the assumption is experienced drivers know better routes, drive smoother and handle cattle calmer. In addition, research shows for all drivers that cull cows and calves have an increased chance of being under loaded in the jail/doghouse and nose compartments, which increases injury.

In another study, 673 cull beef cows were hauled from southern Manitoba to a packing plant in Alberta in winter. Eighty carcasses were bruised, with the most severe bruising occurring in cows transported in the jail/doghouse. Also, the longer cows waited in the trailer the more bruising occurred.

“Even the best transporters, conditions and training can’t compensate for poor loading decisions,” Schwartzkopf-Genswein says.