Fatigued Cattle Syndrome: What It Is and What to Do About It

As spring rolls into summer, the fairly common issues of bloat and other digestive abnormalities begin to show up more frequently in feedlot cattle. As temperatures move higher in June, July and August, a less common but equally concerning problem producers, veterinarians and processors see more of is Fatigued Cattle Syndrome.

At its core, the problem is a metabolic disorder – likely a multi-factorial problem – that reduces the mobility of fed cattle presented to abattoirs, according to Jacob Hagenmaier, veterinarian and director of clinical services for the Veterinary & Biomedical Research Center, based in Manhattan, Kan.

A similar problem exists in hogs called fatigued pig syndrome (FPS) – hence the name for the problem in cattle. The USDA says the “predisposing factors contributing to FPS can be characterized as the pig, environment/facility, people, transport, and processing plant.” Similar factors are at play in cattle.

When Was The Problem In Cattle First Identified?

The syndrome was first reported in 2013, when there were observations of cattle arriving at packing plants that were “nonambulatory, slow and difficult to move, and, in some cases, sloughing their hoof walls in packing facilities” (Cima, 2013; Vance, 2013).

“Those cattle did not possess obvious signs or cause of lameness,” Hagenmaier says. “In feedlots, we tend to think of foot rot, musculoskeletal injuries or digital dermatitis as the most common causes of impaired mobility.

"These were cattle presenting with decreased mobility and muscle tremors but with no specific cause," he adds. "So that made us begin to ask some questions about what exactly was driving this new clinical presentation in fed cattle at the time of shipment for harvest.”

In some cases, severely affected cattle recover and pass ante-mortem inspection whereby they can enter the food chain. But in other cases, the animals that become non-ambulatory or downer animals have to be euthanized and can’t enter the supply chain.

The problem was and is an animal-welfare issue and can create a significant financial loss for owners, says Dan Thomson, veterinarian, educator at Kansas State University and host of DocTalk TV.

“There isn’t a more expensive dead than one that’s been delivered to a packing plant; it’s a big-time hickey to your bottom line,” Thomson said during a discussion with Hagenmaier on DocTalk.

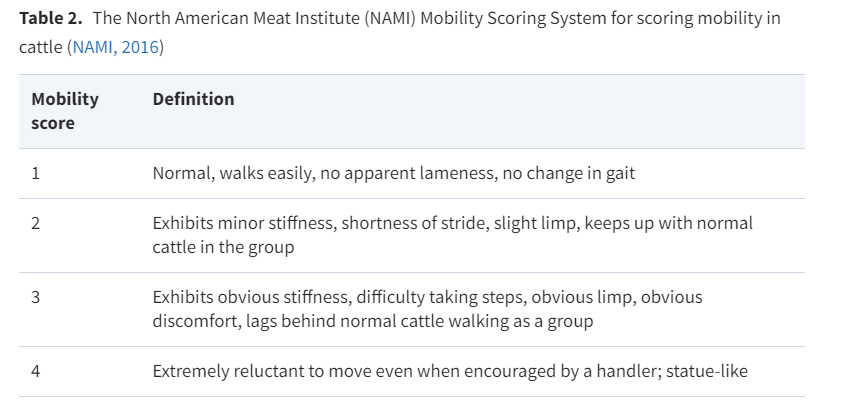

A locomotion scoring system specifically tailored to this syndrome for fed cattle was developed as a resource. This resource “was created as a collaboration between NAMI’s Animal Welfare Committee and industry experts and is known today as the NAMI Mobility Scoring System,” reports a Journal of Animal Science article published in 2020, Animal welfare in the U.S. slaughter industry—a Focus on Fed Cattle.

“I think it’s really important that people understand what these animals (that score a 4) look like,” Thomson says. “We have a syndrome in horses called tying-up, and that’s what these cattle look like at the plant.”

Hagenmaier says metabolic acidosis is very often present in cattle that score a 3 or 4 on the mobility system. “High lactate is a key blood abnormality involved with this disease. When God made cattle, the one thing he made them deficient in is lung capacity – their ability for aerobic respiration to get oxygen to supply all those muscles,” he says.

In addition, Hagenmaier speculates that increased body weights at the time of shipment for slaughter may contribute to a higher prevalence of cattle with impaired mobility at the abattoir.

“If you go into the USDA data, (you’ll see there’s) 10 pounds of carcass weight that we've been adding on these animals every year since approximately 2010.” he says. “So the question is, is our musculoskeletal system keeping up with as many pounds as we're putting on?”

Soon after fatigued cattle syndrome was identified, some beef industry members proposed the problem was more prevalent in cattle that had been fed a beta-agonist, but research to date has indicated that is unlikely to be the case. Kansas State researchers and others continue to evaluate beta-agonist products. You can learn more about their work here: Beta-agonists, The Environment and Cattle Fatigue

Practices To Help Prevent The Problem

There are multiple strategies to reduce the incidence of Fatigued Cattle Syndrome, including how cattle are handled, fed and managed from arrival at the feedyard to the time they leave for slaughter.

Here are seven practices Hagenmaier and Thomson recommend to minimize the potential for the Syndrome to develop.

1. Feed cattle a good trace mineral package. “We want to make sure we don’t have any nutritional deficiencies in any of our trace or macro minerals,” Hagemaier says. “Make sure you have a well-rounded nutritional program, which most feedlots do.”

2. Use low-stress handling practices at the yard and at loadout. “If you and I were to sit on a couch and eat potato chips all year and then be asked to walk a mile, it might be a little difficult for us, right? So be respectful of the events of the day (you ship cattle) relative to what that animal has been doing 150 days on feed prior to that,” Hagenmaier says.

3. Consider how you manage the loadout process and the time leading up to it. To minimize stress, plan on staging cattle near loadout a day or two prior to shipping.

4. Evaluate who you have working cattle in the pen and moving them out of the pen. “You want people who are familiar with the cattle working them, if at all possible. You also need a sufficient number of people on hand to do the job, which can reduce the stress on the animals,” Thomson says.

Along with that, walk animals from pens to loadout, taking plenty of time in the process so the animals aren’t rushed and don’t run.

5. Determine what you’re asking the cattle to do in preparation for loading. “If you can have them go out the front of the pen, where they normally congregate that might be less stressful than going out the back of the pen,” Thomson says.

6. Don’t overload transport systems with too many animals. When crushing injuries occur, creatine kinase, a so-called “leakage” enzyme that is released during rhabdomyolysis, increases in circulation. It’s the most widely used enzyme for evaluation of muscular disease in cattle, according to Cornell University’s eClinPath, an online textbook on veterinary clinical pathology.

Hagenmaier says the measurable presence of creatine kinase is very suggestive of severe cases of Fatigued Cattle Syndrome.

“What's interesting to me is when we have tub-based systems, we talk about not overloading the tub with regards to arrival processing, but loading fat cattle is no different,” he adds. “And actually, they're at more of a risk, because we have that much more weight and that much more force so that we can cause some pretty severe crushing injuries when we're trying to load too many heavy cattle at one time.”

7. Keep cattle well-being front and center at every stage of the process. Be set up to provide adequate nutrition, water, shade, pen space, etc. By taking these into consideration, Hagenmaier says producers are able to “accommodate fat animals, because their needs are certainly different than those of arriving cattle at the feedlot.”

Feedlot Cattle Health Summit in Kearney, Nebraska on July 12

Label Changes for Implant Use are Coming in June

Good Ideas Can Come from Anywhere, Even If You Can't Understand Them