Truth, Lies and Wild Pigs: Missouri Hunter Prosecuted on Presumption of Guilt?

When Michael Bennett loaded eight squealing pigs into the back of a Ford pickup truck, eased off sale barn gravel and onto highway blacktop heading north, the wheels began turning on one of the most bizarre feral hog stories on record, and a legal fiasco that unleashed a litany of questions over guilt, innocence, and state power.

After buying multiple pigs at a Missouri sale barn in 2017, Bennett began a surreal journey to the cusp of state prosecution for alleged violations of law—specifically related to charges stemming from the intentional release of pigs into the wild. Less a whodunit, Bennett’s account is an uncomfortable clash between the bounds of reasonable doubt and the certainty of governmental authority.

“Common sense should tell people something is off with the way the government tried to make me look,” Bennett says. “I ain’t no choirboy, but I never did nothing they said. I believe they wanted to make an example out of me, and all they needed was suspicion, instead of facts, but they sent the facts to hell.”

An Empty Pen

On Aug. 11, 2017, Bennett, 25, and a friend, Nathan Wolfe, split the costs of eight pigs at Texas County’s Summersville Stockyard in Summersville, Mo., in the southeast corner of the Show-Me State, roughly 20 miles north of the Arkansas line.

Swine in his truck bed, Bennett departed from Texas County, passed through Shannon County, and arrived at his Jadwin community home in extreme southern Dent County. That night, according to Bennett, he put one pig to immediate slaughter and deposited seven of the animals, earmarked with USDA Brite Tags, in a dilapidated pen adjacent to his trailer. The pen’s fencing, made from 2”x4” wire, formed a pie-shaped enclosure connected to three trees serving as posts, creating a triangle approximately 12’ long and 7’ wide at the base.

The following morning, Bennett insists, he awoke to an empty pen. Every pig was gone. “I was upset because the pigs escaped and I lost a lot of money,” he says, “but I didn’t have no idea I was fixing to be the No. 1 example of illegal hunting for the whole damn state.”

The Pig Bomb

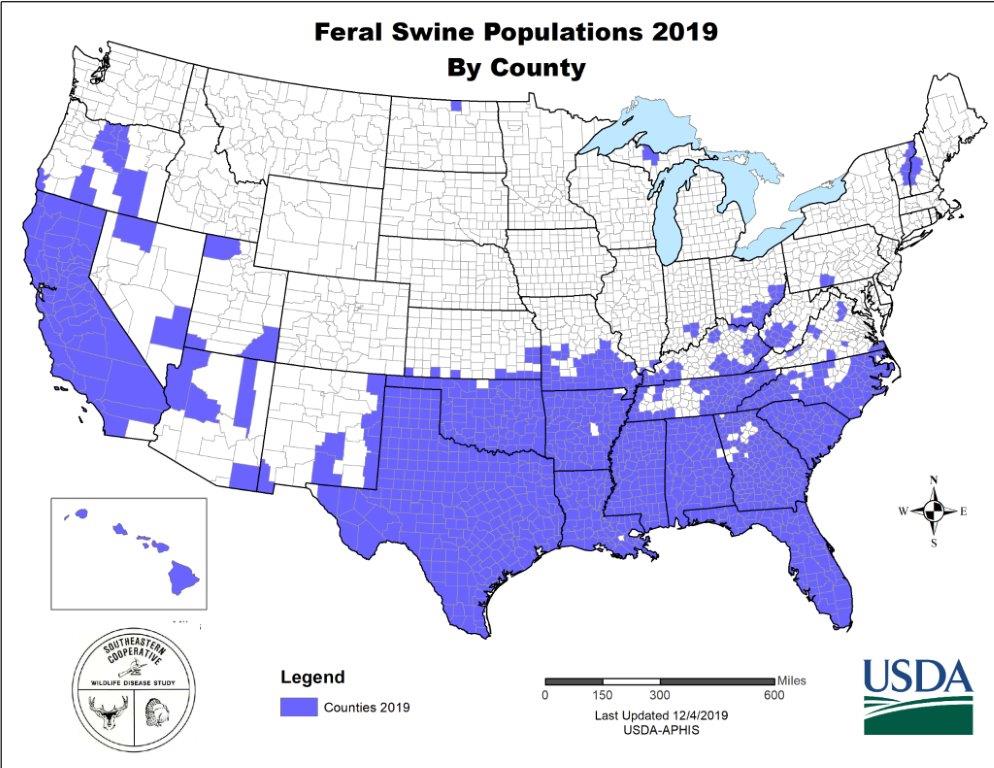

Wild pigs are a rapacious species, costing the United States as much as $1.5 billion in damage each year, according to the National Feral Swine Damage Management Program (NFSDMP). Nationwide population estimates vary, but Jack Mayer, manager of the Environmental Sciences and Biotechnology Group at the Savannah River National Laboratory in Aiken, S.C., places the approximate U.S. wild pig tally at 6.3 million, with an overall estimate ranging between 4.4 million to 11.3 million.

Over the past decade, the increased presence of wild pigs has become a significant political and wildlife issue in Missouri. Hunting wild pigs is legal in Missouri, but only on private land. Wild pigs reproduce at an outrageously high rate, with sows capable of delivering two litters (average of six piglets per litter) in 15 months. Females are reproductively capable at five to six months, fueling the multiplier effect. Generally, wild pig biologists place the “control” bar at roughly 66% to 75%. In theory, if a given area has a wild pig population of 100,000, then 66,000 to 75,000 must be killed each year—just to keep the population at a floor of 100,000. Simply, sustained wild pig control is a herculean task.

The heaviest populations of wild pigs in the U.S. range in the Southeast, ravaging ground between Florida and Texas, but population numbers have recently climbed in Missouri. According to the Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC), the number of wild pigs in Missouri is a mathematical blank—an unknown.

However, a Mark Twain National Forest publication (Forest Reflections 2017, page 10) released in June 2018, contradicts the absence of a wild pig approximation, and projects numbers at “an estimated 20,000 – 30,000 feral hogs in the State of Missouri.”

Additionally, during testimony before the Missouri Legislature in February 2020, Dale Nolte, program manager for the USDA APHIS National Feral Swine Damage Management Program, pegged the wild pig population in Missouri at up to 100,000.

By calendar year, wild pig totals removed through trapping in Missouri are on the rise, and the statistics are touted by MDC as indicative of an increasingly successful eradication program: 5,358 in 2016; 6,567 in 2017; 9,365 in 2018; 10,945 in 2019; and 12,635 in 2020. Yet, with no MDC overall wild pig population estimate as a measuring tape, the trapping statistics lack context. Simply, the trapping numbers can be viewed as proof of effective control, or as evidence of an increase in wild pig presence.

Why? Because if the Mark Twain tally of 20,000-30,000 wild pigs is ballpark accurate, or if Nolte’s estimate of a range up to 100,000 wild pigs is correct, MDC’s wild pig trapping numbers are remarkably far below conventional control rates (66% to 75% control bar).

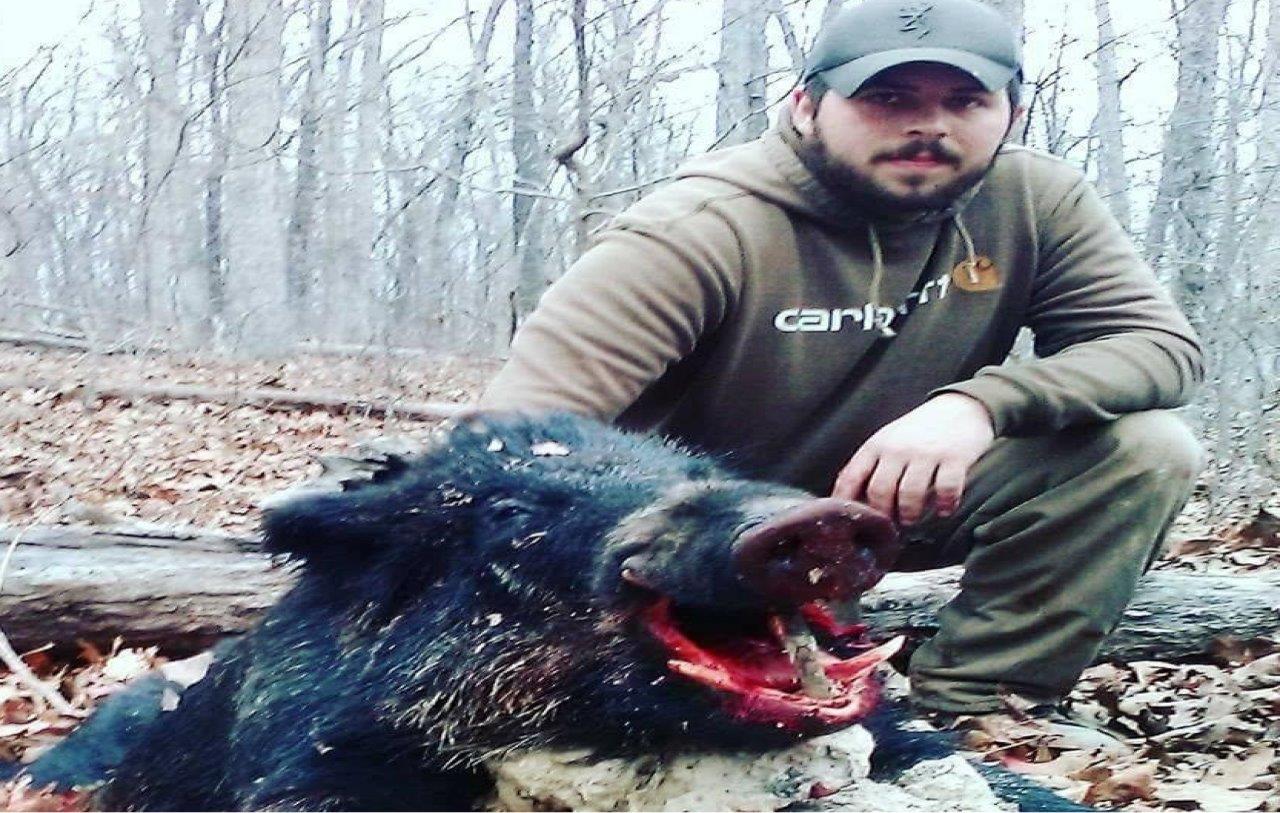

Regardless of present numbers, MDC officials (as well as wildlife officials in other wild pig-afflicted states) place heavy attribution for the expansion in wild pig geography and increase in wild pig populations to illegal releases; i.e., human transport of individual or small groups of wild pigs in order to purposefully boost hunting potential. Boiled down, MDC believes the sound of wild pig expansion is often the crunch of truck and trailer tires on gravel.

Whether the numbers are right or wrong, such were the tangled background threads of Missouri’s wild pig tapestry when MDC placed its legal eye on Bennett, convinced he bought pigs at the Summersville Stockyard and released them with the intent to boost feral hog numbers and augment hunting. Bennett contends he was the victim of overzealous game wardens, but from MDC’s perspective, Bennett was a proven outlaw.

Guilty? Innocent? A battered adage is fitting, no matter the vantage point: The devil is in the details.

Mulefoot Conspiracy

On Sept. 2, 2017, less than 2 miles from Bennett’s mobile home, a nearby property owner in Shannon County shot and killed two pigs, each marked with an ear tag, denoted by the USDA identification numbers: 43AT9565 and 43AT9567.

Several weeks later, on Sept. 29, after tracing the pigs’ identification numbers, Conservation Agent Brad Hadley, MDC’s representative in Shannon County, called Todd Hornback, then-owner of Summersville Stockyard, seeking processing paperwork on the two pigs in question.

Cutting hay an hour from the sale barn, Hornback answered his cell and listened to a series of requests from Hadley. “He (Hadley) said he was at my business place and had a search warrant on his console that he was ready to use,” Hornback remembers. “He was direct and said I’d come to him, or he’d come to me. Either way, Hadley said I was going to talk to him.”

At a minimum, Hornback notes, Hadley wanted information—backtags and paperwork—on everyone involved in Bennett’s pig transaction. “I didn’t have any idea what he was talking about,” Hornback says. “We were moving a lot of livestock and it was impossible for me to recall specific details on a handful of hogs.”

Gathering the corresponding paperwork, Hornback then drove to a designated grocery store parking lot to meet with Hadley and another wildlife officer. Hornback contends that prior to the parking lot meeting, Hadley and MDC had already reached a two-pronged conclusion: First, the two pigs were definitive proof of an illegal release into the wild by Bennett, in order to boost feral hog numbers. Second, the two pigs were evidence of a wider conspiracy between multiple players—including Hornback—within the hog hunting community to transport, sell, purchase, and release pigs into the wild.

“They were there from the get-go assuming I was involved in a wild pig scheme; I know it,” Hornback says. “I got out of my vehicle, and Hadley stood in front of me, and the other guy got behind. I know exactly what was happening because they assumed I was a criminal, and was part of some crazy gang buying wild pigs from other criminals, then selling the wild pigs in my barn to people who were secretly releasing them. Kinda like a network.”

According to Hornback, Hadley displayed smartphone pictures of the two dead pigs in question, and handed Hornback the cell for a closer look. Hornback couldn’t contain his disbelief: “Something was funny about the pictures right off the bat; just didn’t look right. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. Thank the Lord above, I zoomed in and saw mulefeet. I told them in black-and-white: ‘Those are not even wild pigs, they’re mulefoot hogs.’”

Hadley’s reaction, according to Hornback, was of shock. “Both Hadley’s and the other fella’s jaws hit the ground, and they didn’t have a clue what I was talking about with mulefoots. I knew right then these guys may have been wildlife officers, but they sure as hell couldn’t even identify what was or wasn’t a wild pig.”

(MDC was contacted by Farm Journal through telephone and email, but declined to answer any questions about the Michael Bennett case or Brad Hadley’s involvement.)

The two pigs, as with all the pigs purchased by Bennett, were mulefoot hogs, among the most distinct porcine breeds in the United States, likely dating back to Spain’s North American arrival in the 1500’s, and possessing a unique calling card—an unmistakable, non-cloven hoof.

“Hadley and the other guy were lost. I told them, ‘Mulefoots are special and sometimes have their own paperwork and it’s their own breed.’ Hadley seemed confused, but he shook my hand, left me alone, and drove away,” Hornback recalls. “That was it. They didn’t want to hear anything else from me.”

Hadley departed with sale barn tagging records, incoming consignment and outgoing sales invoices, and the identities of consignor and buyer: Duane Smotherman and Michael Bennett.

“They fingered me as the middleman selling wild game between Smotherman and Bennett,” Hornback adds, his voice rising with exclamation. “Craziest s*** I’ve seen in my life. Who in the hell sneaks around to pay extra for mulefoots out of a sale barn and then releases them into the woods to go feral? And who in the hell releases hogs into the woods and leaves the ear tags in place?”

Enter the Kingpin

Several days later, Bennett was at home preparing for an evening hunt at approximately 5 p.m., loading coyote hounds into a dog box attached to his truck bed, when Hadley pulled onto his property in an MDC vehicle. Escaping the barking din of the dogs, Bennett entered Hadley’s cab to answer questions regarding purchase of the mulefoot hogs. “I already had heard about the two hogs getting shot,” Bennett says, “and when Hadley pulled up and asked me to talk in his cab, I had no problem because I hadn’t done nothing.”

Bennett was no stranger to game wardens. As described in MDC citations 286249 and 286736, on Nov. 16, 2012, Bennett fled the scene after being seen spotlighting deer by two Reynolds County conservation agents. The following day, he was located by the two agents (Eric Long and Matthew Bryant) and admitted to the illegal harvest of an 8-point deer. Bennett pled guilty to “take, attempt to take, or pursue wildlife from or with a motor driven air, land or water conveyance.” In addition, he pled guilty to “take, attempt to take, or pursue wildlife with aid of artificial light.” He paid roughly $700 in fines and court costs.

In discussing the 2012 spotlighting incident, Bennett says his conviction was justified. “Those game wardens got me because I done it and I was guilty. I was 19 years old and made a bad mistake, but that shouldn’t make people automatically think I’m guilty of everything in the future. I think the conservation people figured I had to be guilty again over the pigs and jumped the gun.”

According to Hadley’s official report from his visit to Bennett’s residence: “I asked Bennett to tell me what happened and he said, ‘I bought 'em at Summersville, brought 'em home, put 'ern in my pen, they got out.’ I asked what kind of pen Bennett has and he said, ‘It's just an old pen.’ I asked Bennett what kind of hogs they were and he said, ‘Mulefooted.’ I asked Bennett if he knew where they came from and he said, ‘I just bought 'ern at the sale barn, is all I know.’ I asked Bennett if he had any left and he said, ‘No, they all got out.’”

Following the initial conversation, Hadley and Bennett exited the truck and walked around the trailer to the makeshift pen. Again, from Hadley’s report: “As we looked at the pen Bennett told me he had put the hogs in there when they got back that night, "...'cause it was midnight when we got in, and I was gonna build 'ern a new pen the next morning.' I did not ask and Bennett did not say whether, at the time he bought the hogs, he already had the supplies bought to build this pen or the feed that would have been necessary for them. Bennett did volunteer that, ‘...they was about twenty-five pound pigs when I bought 'ern.’ I asked Bennett how much he'd paid for the hogs and he said, ‘...twenty or thirty dollars.’ I asked Bennett if all seven had come here, to this pen, and if all seven of them had got away from here and he said, ‘Yeah. I was gonna fatten' em up and butcher 'em.’”

According to Bennett, the presence of ear tags in both mulefoots killed on nearby land was of no interest to Hadley. “I told him (Hadley) taking out the ear tags would make it so the pigs could never be traced, but he said tags fall out and I would have known they’d drop out in a few weeks.”

The proposition that a seasoned hog hunter (Bennett) would leave ear tags on the pigs is unreasonable, Hornback insists. Additionally, Hornback says any belief the tags would fall out rapidly from the pigs’ ears is incorrect: “No way the metal tags are coming out on their own unless ripped out. An owner, whether experienced or not, can get the tags out in seconds by easy cutting, and all evidence of ownership is gone. I guarantee you Michael Bennett knew that.”

Hadley next asked for a written statement reiterating the conversation—and then read Bennett a Miranda warning, and told Bennett citations would probably be issued. After the written statement was completed several minutes later, Hadley declared he would meet with Dent County Prosecutor Andrew Curley for further action.

(The Dent County Prosecutor’s office was contacted by Farm Journal through telephone and email, but declined to answer any questions about the Michael Bennett case.)

In total, the interview, walk-through, recitation of Miranda rights, and written statement lasted 45 minutes. Hadley drove away from the alleged scene of the crime, about to compile a “Conservation Agent’s Statement to the Prosecuting Attorney” in order to set the legal wheels in motion toward the prosecution of Bennett over the accusations of pig release.

Hadley’s report, issued on Oct. 24, 2017, was roughly 2,700 words, and contained speculation and hog hunting conspiracy allusions, and concluded with a hazy final paragraph: “This investigation has documented that a known feral hog hunter sold through the Summersville Stockyard, LLC seven hogs that were ear-tagged with US Department of Agriculture (USDA) "Brite Tags" by sale barn employees, and those hogs were bought by another known feral hog hunter. That buyer, Michael L. Bennett, had made no provisions to control and contain the movement of those hogs and all seven subsequently became free-roaming. Two of those free-roaming ear-tagged hogs were subsequently shot and killed by the neighbor of the buyer of the hogs, while the remaining five are apparently still free-roaming at the time of this report.”

Bottom line: Bennett, whether guilty or innocent, was set to face charges that appeared to rely on conjecture.

Further, according to inference within Hadley’s report, there was an origin source for the conspiracy: Enter Duane Smotherman, the alleged kingpin, and his herd of mulefoots.

A “Known Hog Hunter”

“It’s a big, fat, total lie,” says Smotherman. “I never met Michael Bennett before he bought the hogs. I’d never seen him before this or knew of him, and anybody who says I gave him or anyone else a tipoff to come buy hogs at the barn is a damn liar too. It’s the biggest bunch of mess I’ve ever heard, but that is exactly what Hadley is getting at between the lines.”

Hadley specifically labeled Smotherman as a “known hog hunter” and a landowner with acreage adjoining a conservation-controlled area where MDC had trapped 38 feral hogs from May to October 2017, on land within 4 miles of Smotherman’s home. Further, Hadley states: “I told Bennett that the person (Smotherman) who brought the hogs to the sale barn was known to us to be a hog hunter and that it was a bad connection when we have one hog hunter selling hogs through a sale barn to another hog hunter who subsequently allowed those hogs to get loose.”

Smotherman, 70, raises cow-calf pairs in Shannon County and owns 787 acres alongside Birch Creek. Mulefoot hogs, more as a hobby instead of livelihood or side-stream income, have maintained a long-time presence on his farm, and Smotherman has sold the breed to multiple sale barns over several decades. “Hadley talks about 38 feral hogs being trapped by MDC close to my house, and what he means is that I’m the one who released them on purpose. It’s not a word true and I’ll say all of this under oath in a heartbeat.”

Despite being mentioned in Hadley’s report as the possible point source for Bennett’s hogs, Smotherman claims he was never approached for an interview or testimony. Again, according to Smotherman, neither Hadley nor the Dent County prosecutor called him for comment. “It’s not a tricky question,” Smotherman says. “If they really believed that I was the behind all this, why in the hell wouldn’t they question me? No, it was much easier to throw my name in there and muddy up everything to make Bennett look even worse. Didn’t nobody at the Conservation Department or at the prosecutor’s office think maybe, just maybe, this ain’t true?”

“The whole deal makes no sense,” he continues. “It’s almost like somebody was waiting to throw my name as a hog hunter out there just to see what might stick with the prosecutors, no matter how crazy.”

Smotherman’s words poke at a peculiar facet of Bennett’s prosecution: The existence of a “Hog Hunter Contact” database compiled by Hadley. Again, wild pig hunting in Missouri is legal on private land with the landowner’s permission, yet Hadley, and by proxy MDC, maintained an unofficial file for the purposes of keeping tabs on individual wild pig hunters—legal or not. Smotherman was in the file—along with 70 to 80 other Missouri citizens.

Recklessly? Knowingly?

After Hadley turned his report over to Dent County Prosecutor Curley, pig release charges were levied against Bennett. (Missouri Statute 270.260 makes it a crime for a person to recklessly or knowingly release any swine to live in a wild or feral state. The statute also indicates the accidental escape of domestic swine is not a crime.)

Bennett faced seven misdemeanor charges of releasing swine into the wild, with each count carrying a potential sentence of one year in jail and a $2,000 fine.

When the Missouri Hunting & Working Dog Alliance (MHWDA), spurred by communications director Missi Ferguson, caught wind of the state’s actions, MHWDA began raising money for Bennett’s legal defense. Enter a bulldog attorney: Jason Coatney.

Coatney grew up on a farm in Greene County in southwest Missouri, and was highly familiar with the nuances of livestock production. The government’s position was “outrageous,” according to Coatney’s conclusions. “It was a misdemeanor charge, but Michael was facing $14,000 in fines. No way. We wanted people to hear the facts of this case and we wanted a jury trial.”

“MDC wanted to stomp the hell out of a backwoods guy who likes to hunt hogs and fits the profile of a poster child because he has past deer violations,” Coatney continues. “Would anyone on a jury believe he’s going to pay $235 for eight pigs and then let them go, when he can easily get pigs for free and let those go instead? Or that he’s part of this crazy hog hunter network with Smotherman? Or that he left in the ear tags so they basically broadcast: This is Michael Bennett’s pig? Bennett is country and can find pigs anywhere, and he damn sure doesn’t need to buy them in a sale barn.”

On Sept. 26, 2018, three weeks before Bennett’s trial, Hadley was deposed by Coatney. Taken under oath, Hadley’s responses during the 50-minute deposition are seemingly contradictory and uncertain. Under Coatney’s prodding, whatever case the prosecution had built against Bennett likely was destroyed by the end of Hadley’s on-the-record testimony.

COATNEY QUESTION (Q): What is it you're going to tell the jury?

HADLEY ANSWER (A): As far as what?

Q: Whether he (Bennett) knowingly or recklessly released these swine?

A: I don't know that it makes any difference.

Q: It makes a huge difference, sir. So what is it you're going to tell them?

A: I don't know that it makes any difference, knowingly or recklessly, either one.

Q: Okay. So do you believe he knowingly released the swine?

A: Again, I couldn't speak to that to say specifically that he did this on purpose to release swine.

Q: Do you believe he recklessly released the swine?

A: I believe anyone should have known that that pen would not hold swine.

Q: Okay. So then you believe he was negligent in putting the swine into the pen?

A: Yes.

Later in the Coatney-Hadley exchange:

Q: ...you agree that you're saying to him that he wasn't going to say he brought the hogs home knowing they would get out in hopes of having hogs to hunt closer to home in Council Bluff? Is that what you're going to tell the jury that that's what he was doing?

A: No

Q: You don't believe that that's what he was doing?

A: I don't know.

Q: Okay. You say here that you don't think it, right? You weren't going to say it. What does that mean to you?

A: It means I'm not going to come out and say that you did this because I don't know what you did.

Q: Okay. Well, you charged him with a crime based upon—I mean, the State has charged him, but you're the person who provided this information.

A: Yes

Q: You came over and met with the prosecuting attorney, did you not?

A: Yes, I did.

Q: Do you think that you lobbied him (Prosecutor Curley) to bring charges?

A: I presented material, I would like charges brought.

Q: Did you communicate to the prosecuting attorney that there's a major problem and that you need to prosecute somebody for releasing swine into the wild?

A: Yes, I probably said we would like to do something with this.

Q: So you were looking for a poster child for the problem that you had of swine in the public, correct?

A: I was looking for a case that we could make in the public. It’s not the easiest thing in the world to find somebody releasing hogs.

Continuing in the Coatney-Hadley exchange:

Q: So do you believe that he purchased these animals to take them home to release them so he could hunt?

A: I believe he purchased those home—those animals, took them to his house, put them in the pen and they escaped, they got out…they—whatever, however it happened, I don't know.

Further in the Coatney-Hadley exchange:

Q: My question is: Do you believe he purchased these pigs and brought them home for the purposes of allowing them to escape to go out into the woods so he would have something to hunt?

A: I don't know whether he did that or not.

Q: And you're not going to tell the jury that he did that?

A: No, I'm not going to tell the jury he did that. I can't say exactly what he did—what his purpose for doing any of this was.

More, from the Coatney-Hadley exchange:

Q: Okay. So what is it that you're going to say to the jury that says that he either recklessly or he knowingly released these swine into the wild?

A: He bought the hogs, they got to his place, they left his place.

Stunningly, over a year after obtaining search warrants, conducting an investigation, and presenting the government with an official report that was the trigger for the prosecution of Bennett, Hadley stated in on-the-record testimony that he did not know motive, intent or purpose related to Bennett and the wild pigs. Piling on the irony, Hadley explicitly stated he would not offer the jury any definitive conclusion on what occurred.

Hadley’s deposition was a genuine head-scratcher. Weeks prior to the official kickoff of the court proceedings, Hadley, the prosecution’s main witness and spearhead in the pursuit of Bennett, was stuck at: “...they (Bennett’s pigs) escaped, they got out…they—whatever, however it happened, I don't know.”

According to the deposition, Hadley had personal belief of Bennett’s guilt—and nothing else. Yet, personal belief and prosecution are separated by a legal mile. Bottom line, Hadley’s deposition served as a sledgehammer to the ankles of the prosecution’s case.

“Hadley first said Michael did it on purpose so he could go hunt the pigs, but when that sounded like horses***, he said the pen wouldn’t hold them anyhow and that was illegal,” Coatney explains. “It was unreal, because when Hadley, the guy who represented MDC and had been the champion of trying to get Bennett, was put under oath, it was easy to see there was no evidence—just speculation.”

“People need to pay attention to these kinds of cases,” Coatney adds. “This one involved Michael Bennett, a country guy with little sophistication, but the State could have been going after anybody.”

Hog Hunter Database

A sidecar of Bennett’s case, yet an alarming facet, remains the database on Missouri hunters compiled by Hadley.

COATNEY QUESTION (Q): Why are you collecting data on people that if they’re not doing anything illegal?

HADLEY ANSWER (A): I collect intelligence information from every contact I make. Things that you learn during in this contact may be of assistance to you in the next contact.

Q: You have other contact information sheets for when you encounter somebody who’s maybe spotlight a deer?

A: No, not necessarily.

Further in Coatney’s questioning:

Q: Do you—you don't disseminate these reports to other agents?

A: I don't believe I have.

Q: What is the objective in inputting this data and keeping these records? What are you trying to accomplish?

A: Just to know the hog-hunting community.

Q: Okay. And so that's the hog-hunting community for what counties?

A: Wherever they might occur.

Q: Okay. And what's their reaction to what it is that you're doing here with these two documents?

A: I've been encouraged, as far as I know. Everybody thought it was a good idea, so...

Q: So is it fair to say then, that in reviewing all of the contact reports, were they all generated by you or did you have others that were generated by other agents?

A: I had other agents that sent me information.

Q: But you generated those reports?

A: Yes. I entered it in the database.

Q: Okay. And is this -- as you sit here today, do you have a present recollection as to how many of these contact sheets that you have in your possession?

A: I'd say 80, 90.

Further...

Q: And for each one of those contacts, you've created this type of a sheet, and you hold that database in your own computer?

A: Correct.

Q: And you don't disseminate it to anybody else in the department?

A: No.

“It’s no wonder Hadley jumps to conclusions about a ‘known hog hunter,’ who was Smotherman, supposedly passing along hogs to another hog hunter, who was Bennett,” Coatney says. “He gets these information forms that he’s filled out, for a database that he’s prepared, and he’s also the repository for the database. However you want to describe it, it’s a government employee keeping under-the-table files on private citizens that he admits may be completely innocent.”

“When you have state officials keeping hidden databases on hunters that are behaving in an entirely legal matter, and the database may or may not be disseminated to other officials, it makes private citizens a little leery.”

Pulling the Handbrake

With Hadley’s deposition in hand, Coatney was convinced the prosecution lacked a submissible case, and pressed hard for a jury trial, demanding the whole ball of wax be rolled before the public. On Oct. 1, Curley asked the presiding judge (Dent County Associate Court Judge Brandi Baird) for a continuance—a delay—and was denied: Trial the following week.

However, on Oct. 11, Curley pulled the handbrake on the case, dismissing the charges against Bennett. According to the The Salem News, Curley stated the following via press release: “I originally filed the charge because the probable cause statement indicated there wasn’t any evidence to believe the pigs were ever placed in the pen. This led me to believe the agent had fully inspected the pen and had sufficient evidence to believe the hogs were never placed in the pen but released directly into the wild by Michael Bennett.”

“Following the (Sept. 26, 2018) deposition, my understanding of the case changed drastically, and I believe it would be impossible to convince 12 jurors the defendant was guilty of this crime,” Curley continued. “A jury would likely see this as an accidental escape.”

Coatney contends finding 12 impartial jurors would have been an extremely difficult task. “It was over. When Curley wasn’t allowed a continuance, he dropped the case. Finished. The judge was about to call in 100 prospective jurors just to find 12 people, and that’s the kind of jury pool number called in for pedophile cases. Why? I believe they knew it was going to be tough to find 12 jurors out of the gate that weren’t alarmed by the Conservation Department’s behavior.”

Significantly, despite Hadley’s admissions during the deposition, and after Curley abandoned the case, MDC continues to champion the performance of Hadley in the pursuit of Bennett, describing his actions as “a thorough investigation.”

From a March 2020 MDC statement sent to Farm Journal: “The Department appreciates the efforts of Agent Hadley and Prosecuting Attorney Curley to conduct a thorough investigation and file charges for the unlawful release of swine back in 2017. While disappointed, we understand the prosecutor’s decision to ultimately dismiss the charges, and the inherent difficulty in proving the culpable mental state of Mr. Bennett. The law requires proving beyond a reasonable doubt that hogs were knowingly or recklessly released.”

Bennett’s case is highly troubling to Coatney, and the Missouri attorney believes a political issue became the spur for overreach by a government agency. “Hogs are breeding like rabbits here and some people blame hog hunters. Whatever position you take, there is no denying feral hogs are a hot political issue in Missouri. You’d think that somebody at some level in MDC would have seen the total lack of evidence against Michael and said something before it got right to the edge of trial, but as far as I know, nobody said a word. MDC believed they had an easy target in Michael, but the facts said otherwise.”

“I’ve seen a lot of things in my career,” Coatney concludes, “but I don’t think I’ve ever seen a stretch like what MDC tried to pull against Michael Bennett.”

Unanswered Questions

Fair question: What would have happened to Bennett without the intervention of Missi Ferguson, MHWDA, and Jason Coatney? Also, was Smotherman next in line to be prosecuted?

“How could the Conservation Department do all this with no evidence?” Smotherman asks. “I’m not even asking for reasonable doubt, just give me some common sense. Nobody moves hogs, especially mulefoots, to sale barns and then secretly hollers at hog hunters to go buy them. Nobody pays money for mulefoots, and then lets them go, and then leaves in the ear tags. Only a bureaucracy person could believe the government’s story without at least raising some questions.”

Smotherman's contention is echoed by Hornback. “MDC was gonna try to claim I was selling wild pigs through my barn. That kind of government power, based on suspicion, is scary to me and ought to be to everyone, because they were moving forward without any evidence, which is exactly what happened to Bennett, and might have happened later to Duane Smotherman. People need to pay attention to this case because these kinds of things should matter to everybody who cares about what’s right.”

Three years after dismissal of all charges, Bennett reflects back on his near prosecution. “I’m innocent and I never released them hogs. I’m thankful for Missi Ferguson believing that something was not right about my case, and raising money to hire Jason Coatney. Otherwise, I don’t know what I’d have done. How do you fight back against people who can push you anywhere they want based on what they guess happened?”

As one of the oddest feral hog stories on record, the question of how Bennett came within days of a trial procedure due to allegations highlighted by an apparent lack of incriminating evidence, still remains unanswered. In the Dent County prosecutor’s press release issued after the dismissal of all charges against Bennett are 10 key words. The 10 words, tacked on as a caboose to the whole affair, might better have served as the lead sentence of the initial MDC report a year earlier: “A jury would likely see this as an accidental escape.”

For more, see:

The Arrowhead whisperer: Stunning Indian Artifact Collection Found on Farmland

Fleecing the Farm: How a Fake Crop Fueled a Bizarre $25 Million Ag Scam

US Farming Loses the King of Combines

Ghost in the House: A Forgotten American Farming Tragedy

Rat Hunting with the Dogs of War, Farming's Greatest Show on Legs

Misfit Tractors a Money Saver for Arkansas Farmer

Predator Tractor Unleashed on Farmland by Ag's True Maverick

Government Cameras Hidden on Private Property? Welcome to Open Fields

Farmland Detective Finds Youngest Civil War Soldier’s Grave?

Descent Into Hell: Farmer Escapes Corn Tomb Death

Evil Grain: The Wild Tale of History’s Biggest Crop Insurance Scam

Grizzly Hell: USDA Worker Survives Epic Bear Attack

A Skeptical Farmer's Monster Message on Profitability

Farmer Refuses to Roll, Rips Lid Off IRS Behavior

Killing Hogzilla: Hunting a Monster Wild Pig

Shattered Taboo: Death of a Farm and Resurrection of a Farmer

Frozen Dinosaur: Farmer Finds Huge Alligator Snapping Turtle Under Ice

Breaking Bad: Chasing the Wildest Con Artist in Farming History

In the Blood: Hunting Deer Antlers with a Legendary Shed Whisperer

Corn Maverick: Cracking the Mystery of 60-Inch Rows